The Prodigy

‘Out Of Space’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number 5 on November 29, 1992

1.

In 1912, a German chemist called Anton Kollisch was working on a new medication to help control bleeding. He developed a synthetic compound with the catchy name of “N-Methyl-a-Methylhomopiperonylamin”, but his research ended shortly after when the war disrupted supply chains.

After the war, various organizations experimented with variations on Kollisch’s compound. The U.S. military ran trials in the 50s, but those trials were abandoned when they discovered that the substance didn’t kill commies.

Near the end of the 60s, psychopharmacologist Alexander Shulgin started exploring the psychoactive elements of the drug. His grad students had—very eagerly—trialled the drug on themselves and discovered that it made them feel affectionate and chatty.

Shulgin called the drug Window (because it makes you transparent) and started marketing it to therapists. Other companies also sold the drug under names like called Empathy (because it aids couples counselling) or Adam (because it returns you to a prelapsarian state.)

Window/Empathy/Adam had another weird effect: it made music sound really good. An opportunistic businessman called Michael Clegg started selling it in Texas under the name Sassyfras, throwing Sassyfras parties where Texans could merrily dance the night away.

Clegg was a quite dodgy hustler, but he had a knack for marketing. He realised that his product needed a better name than Sassyfras (or Window) he created a new brand: Ecstasy.

The Feds were not happy with the growing recreational popularity of ecstasy, which was on every college campus by 1985.

By 1985, Sassyfras had spread to every college campus in America, and the government were pissed. They made MDMA an illegal substance, and encouraged other nations to do the same. Ecstasy usage soon plummeted across the States.

But now it was popular on the Spanish island of Ibiza, a place that was already home to drugs and great music. Holidaymakers brought ecstasy home to their own countries, so the party never had to end.

Soon, ecstasy found its true spiritual home: a damp, miserable island where the government were working hard to stamp out joy.

2. I’ll take your brain to another dimension

The British working class have a proud history of getting fucked up.

The 60s and 70s saw the emergence of the quirky Northern Soul movement in towns like Wigan and Blackpool. Young people would work their menial jobs all week to earn some cash, which they would then spend on amphetamines so they could up to 72 straight hours just dancing. Not drinking, or fighting, or screwing. Just dancing.

Northern Soul music was mostly Motown and R&B, but nobody cared about the artists or the song. Dancers only cared about the bassline, the rhythm, and the beat, which had to be a minimum of 100bpm.

Northern Soul happened in towns that were already pretty grim, and which became even grimmer when Thatcher started shutting down mines and heavy industry. This was the era of “there’s no such thing as society”, the era of “greed is good” and “fuck you buddy”. Thatcher and Regan were building a world where all human life boiled down to one aspiration: get rich or die trying.

But what if another world was possible?

At this moment in time, there were so many groups who yearned for something different. First, you had the crusties—the people who turned their back on society and adopted alternative lifestyles, living in vans and squats, trying to stay off-grid.

Then you had working-class kids abandoned by Thatcher. Some of these kids fought back through radical politics, becoming communists or anarchists or trade unionists or—sadly—skinhead racists. But most kids don’t want to join a party. They want to go to a party.

On top of all that, Britain had a rapidly growing immigrant community, many of whom faced quite brutal social exclusion. Fair to say, I think, that quite a few of them were also depressed by mushy peas, drizzle, and Showaddywaddy.

All of these disparate groups trying to survive. And then: ecstasy. And dance music.

Here’s a new music with universal appeal. No lyrics, no instruments, no stars, no links to the past, just a DJ providing you with a steady beat. And here’s this drug, this magical drug that makes you feel like you’re soaring.

Hippies talked about peace and love, but ravers really felt it. When you come up on ecstasy, when you reach that perfect zenith, when your body sits into the groove—it’s impossible to hate anyone. It’s impossible to be angry. You are filled with the joy of being alive and being with people.

When the DJ drops the perfect beat at the right moment, something magical happens. You get transported outside of time, space, and identity. You become a feeling, a vibe, a rhythm. Free.

You catch a glimpse of Utopia, the other world they told you was impossible.

3. Find another race

“The government didn’t know what it was. The police didn’t know how to control it. The kids ran it.”—Keith Flint

Rave culture metastasised very quickly across Europe, but Britain is the place where it felt like ravers might actually overthrow the government.

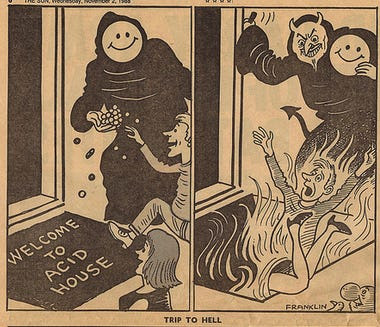

The establishment fought back. BBC banned ‘Everything Starts With An E’ (but were oblivious about ‘Ebeneezer Goode’), while the tabloids made rave culture seem like a death cult.

By 1992, things were reaching a tipping point.

The Prodigy had emerged the previous year as a bit of a novelty act with their first single, ‘Charly’. Around the start of 92, the band met Mr C of The Shamen who, according to Keith, “gave us a patronising pat on the back, and said, if you get a year out of it, then enjoy that year.” The view at the time is that rave music—proper ‘ardkore rave music—was a fad that would die out before it went mainstream.

But The Prodigy did cross over, escaping the illegal warehouse rave scene and making it to mainstream radio. The follow-up singles were hits, and Experience proved that it was possible to make a great rave album. Rave culture was here to stay.

Meanwhile, ravers got their own Woodstock in the form of the Castlemorton Common Festival, a massive illegal rave on public land in the summer of 92. It started when police prevented crusties from hosting the Avon Free Festival. They set up camp in Castlemorton with the help of several techno sound systems, and soon 40,000 ravers were there. It went on for a week.

At this exact moment in history—the latter half of 1992—it feels like something is happening and anything is possible. Maybe rave will save the world. Maybe the youth will rise up, overthrow the government, make MDMA available on the NHS, and create one nation under a groove.

4. Pay close attention

Spoiler alert: nobody found Utopia.

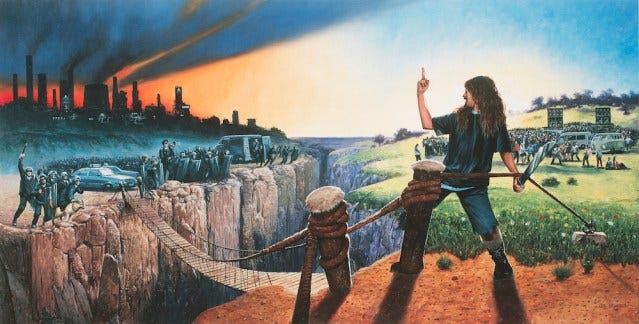

The UK government has a shockingly draconian response to all this. In 1994, mere weeks before The Prodigy dropped their sophomore masterpiece, Music for the Jilted Generation, Parliament passed the Criminal Justice Bill, which banned squatting, gave police greater stop-and-search powers, and criminalised trespassing.

It also specifically banned illegal raves, which it defines as a gathering of 20 or more people listening to “sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.”

Jilted Generation included a lot of anti-police songs, plus this sleeve illustration:

Dance music became more of a commodity, as club promoters realised that they could charge whatever they wanted. DJs became as big as rock stars. The Prodigy became literal rock stars—‘Firestarter’ is a song written for beer, not pills.

When you talk to old-skool ravers who were there in the early 90s, they’ll tell you about an even bigger problem: the drugs turned to shit. Ecstasy became cheaper and more widely available in the 90s, but the purity declined, and pills were often cut with speed or other amphetamines.

A drug-based Utopia was never achievable, of course. The Nazis tried to build an empire based on crystal meth, and that didn’t quite work out (although in fairness they seem to be making a comeback.) Heavy, long-term ecstasy usage can fry the brain in a way that leaves you in a state of anhedonia, unable to feel any happiness, locked out of heaven forever.

The music, however, is still pure and uncut, and still delivers that bump. You can listen to ‘Out Of Space’ while doing the dishes or picking the kids up from school, and a little bit of that excitement comes back. And if you close your eyes and lose yourself in the beat, you can sense another world that’s alive somewhere, waiting for us to find it again.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?