Soul Asylum

‘Runaway Train’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

#7 on November 14, 1993

1.

In 1993, Chelsea Clinton was the world’s most relatable person.

Her dad did a lot of embarrassing dad stuff: playing sax, wearing sunglasses indoors, making wink-wink jokes about how he neeeverrrr smoked pot in college. Chelsea, just thirteen years old, seemed always to be cringing. To make matters worse, America chose to validate Bill’s behaviour by making him “The First Rock’n’Roll President”. He was even invited on MTV for the first (and, to date, only) MTV Inaugural Ball.

The MTV Ball happened shortly after the real inauguration. Bill and Hilary marched onstage to the sounds of their campaign anthem, Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Don’t Stop’, while an adoring crowd greeted them like rock stars. As Bill prepared to speak, Hilary suddenly ran to the wings and returned with Chelsea, who had to be physically dragged into the spotlight.

Chelsea’s body language here in this moment is incredible, silently screaming, “moooooooom, nooooooooo.” She is every teenager who’s been made to pose for a family photo, or model their new sweater, or sing a song for granny.

She is all of us. Je suis Chelsea.

Being the First Teenager did have perks though. Chelsea helped programme the inaugural ball, which meant that she got to invite one of her favourite bands: Minnesota alt-rockers Soul Asylum.

Soul Asylum were small fry in January 1993, but they were in for a wild summer. When they played the White House in September 93, they had become a global sensation and their album, Grave Dancers Union, was on its way to becoming triple-platinum.

Chelsea missed that White House performance (she had math class), but President Clinton was in attendance. He praised the band because:

“They made that wonderful song about runaway children, which had a big impact on young people throughout the country.”

Bill was referring to ‘Runaway Train’, which was promoted by a video that included details of real missing children and teenagers, plus a hotline for anyone with information. The video was a sensation and these days is credited with saving 21 children.

Which is an incredible feat… if it’s true. But it’s a lot more complicated than that.

2. This time I have really led myself astray

First, we need some context.

The phrase “missing children” is pretty terrifying, especially if you’re a parent. It conjures up an image of strangers in vans snatching kids off the street for god-knows-what ends. And this can happen—but it is also very rare. According to the FBI, only 0.1% of missing children cases involve strangers. The rest are either runaways or have been taken by someone known to the child (usually a parent).

Nonetheless, child-snatching is what grabs people’s attention. America saw a number of high-profile child disappearances in the early 80s, leading to widespread panic about Stranger Danger.

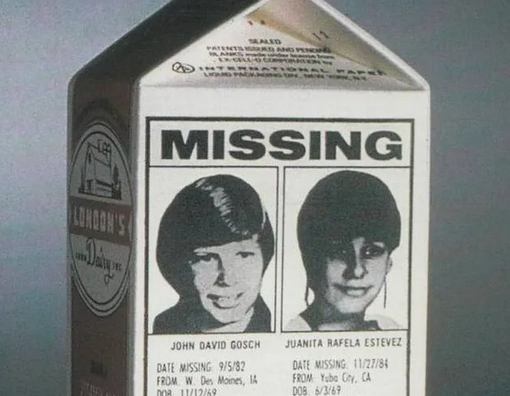

In September 1982, on a crisp Sunday morning, 12-year-old Johnny Gosch left home in Des Moines, Iowa, to deliver newspapers. He was never seen again. Almost exactly two years later, 13-year-old Eugene Wade Martin also vanished while delivering papers in Des Moines.

The paperboy kidnappings put middle-class America on red alert. Some people, including Johnny Gosch’s mother, believed that trafficking rings were snatching children from the street and sending them to countries like Mexico. Right-wing politicians did little to reassure parents, and even Reagan seemed to believe that there was a sinister conspiracy.

One dairy in Des Moines decided that it was time to act. They printed Martin and Gosch’s details on their milk cartons, urging people to contact the police with information. The campaign was a success, and other American dairies followed suit. By 1985, around 700 dairies were putting missing kids on their milk cartons.

Critics of the milk carton scheme, which was wound down in 1996 after the introduction of Amber Alerts, said that it exaggerated the risks of stranger danger and distracted from more important child safety issues. Also, it scared kids, who lived in terror of their faces ending up on a milk carton.

Johnny Gosch’s mother was a staunch defender of the milk carton scheme, but even she admitted that it failed to help the investigation. Gosch and Martin’s disappearances remain unsolved to this day.

3. Seems like I should be getting somewhere

Soul Asylum had released five studio albums before they signed to Columbia, all of which flopped. But then Grunge happened, and suddenly anyone could be a superstar if they played guitar and looked like they didn’t shower.

Grave Dancers Union was heralded by the single ‘Somebody To Shove’, featuring a video by up-and-coming auteur Zack Snyder, who also shot their next video, ‘Black Gold’. Neither track made a significant impact on the Top 40.

For the third single, the band decided to try something different. They met with British director Tony Kaye, best known for doing the Intercity ads in the 80s. He’d listened to their song, ‘Runaway Train’, and completely failed to pick up on the song’s core theme of depression and artistic frustration. Instead, he focused on the word “runaway”.

Kaye had become fascinated with the milk carton thing, which had become a weirdly iconic element of American culture. What if, he suggested, this video acted as one giant milk carton? What if they included photos of real missing kids and tried to find them?

The band loved the idea. Or at least, they reckoned it was better than working with Zack Snyder again.

Kaye’s video for ‘Runaway Train’ has three core elements. First, Soul Asylum perform the track while looking sad and grungy. Then there’s a dramatised narrative showing all the biggest cliches of Stranger Danger: weird guys with candy, people being snatched into vans, young girls walking the street.

During the chorus, the video shows photos and names of around a dozen missing children and teenagers. At the end of the video, Dave Pirner looks straight at the camera and urges people to call if they have information.

Tony Kaye later said:

“The record company were very supportive, although after it was first shown on MTV, they called saying: ‘No kids have come back. Can we replace the faces with shots of the band?’ I said: ‘No, wait.’ Then one came back, and another, and another. And it turned into this miraculous thing.

“The first to come home was Elizabeth Wiles, a teenager who’d run away from home with an older guy. She’d been watching TV with friends, seen herself in the Runaway Train video and called her mom.”

They edited three different versions of the clip, each with a different set of missing people. When the song went international, they released localised versions featuring missing people in the U.K., Australia, and Germany. And because the song was such a hit, millions of people saw each video.

In terms of awareness-raising, ‘Runaway Train’ was an unprecedented success. But did it actually help the kids?

4. Like a madman laughing at the rain

Most of the missing person cases are now resolved, although not happily.

By extraordinary coincidence, two people shown in the U.K. version were victims of the same serial killer. More shocking still, the Australian video featured three victims of another serial killer. There were some other tragic cases in the US, but the majority of these involved someone who was already known to the victim—not Stranger Danger.

Around 21 kids did show up later, not all of them were responding to ‘Runaway Train’, and many didn’t want to be found. Soul Asylum guitarist Dan Murphy met one of the featured kids in later years. He said this:

“On tour, another girl told us laughingly, ‘You ruined my life’ because she saw herself on the video at her boyfriend’s house and it led her being forced back into a bad home situation.”

Recently, Slate magazine tracked down some of the other people featured and found that many of the people featured had run away to escape a toxic home environment. One person, who had fled from abuse, contacted police after seeing herself in ‘Runaway Train’. She was reunited with her family, only for her mother to pull her siblings away, saying, “That’s a stranger. We don’t talk to strangers.”

Another girl had run away at 16, but was 18 when ‘Runaway Train’ released and had already notified her mother that she was safe and well. “I don’t like people knowing my business,” she said, reflecting on her sudden fame. One of the others was eventually reunited with her mother—on the set of The Jerry Springer Show.

Only one person seems to have been happily reunited with their family as a result of ‘Runaway Train’. Good news for that family, but the project can’t really be considered a success.

5. Somehow I’m neither here nor there

So, was ‘Runaway Train’ a good thing or bad thing?

Before we pass judgement, it’s important to note that Soul Asylum have never been cynical or exploitational about this. ‘Runaway Train’ was a hit in spite of the video, not because of it, and they’ve never tried to live off of their “we save kids” reputation. Recent interviews suggest the opposite—they seem reluctant to take credit for any rescues or interventions.

Soul Aslyum tried to do a good deed. They deserve credit, especially as the video could have backfired and tanked their whole career.

However, it was ultimately part of the bigger Stranger Danger moral panic, which distracts from more important conversations about child protection.

Stranger Danger, you see, is a comforting myth. It’s terrifying, but at least it’s something external that you can protect against. You can lock the doors, buy a gun, and keep your children safe. You can convince yourself that every kid has a safe, loving home to which they can return. You can even sing songs to guide them home. And that’s much less distressing than the messy truth.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.