Shaggy

‘Oh Carolina’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number One on March 14, 1993

1.

Musical trends are often the result of one specific hit. ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ was a success, and suddenly the charts were filled with grunge. Cher blessed the world with ‘Believe’; next thing, everyone on the radio sounds like an Autotuned robot.

However, some trends seem to appear spontaneously. Why did so many late-80s dance-ey pop songs use that one “aw yeah” vocal sample? We may never know.

Early 1993 brought us one of these spontaneous trends. It’s something that you wouldn’t have noticed until you looked at the Top 10 and saw this:

Reggae music hadn’t been popular for a long time. Now, suddenly, the three biggest chart hits were reggae (or, in Snow’s case, reggae-adjacent).

Coincidence? Maybe. But look at the chart from just two months later:

We also had huge reggae and reggae-adjacent hits from Bitty McLean and Apache Indian, plus a year of absolute chart domination by Chaka Demus & Pliers.

1993 was The Year of Reggae. But why? Why did pop audiences suddenly go crazy for Caribbean rhythms?

2. Come bubble ‘pon me

To understand this, we need to go back and look at how the Jamaican music scene develop.

Previously in this newsletter, we talked about how Jamaica has had a thriving music scene since the 1950s, and how immigrants introduced this music to Britain, eventually giving us things like the 1992 rave anthem ‘On A Ragga Tip’ by SL2.

One thing we didn’t discuss was how Jamaican people listened to music, which is a vital element of any music history. For example: rock’n’roll happened because people in the US had radios and record players, which created a market for snappy, youth-oriented pop songs.

Radios and record players were a luxury in 1950s Jamaica, especially in low-income communities. These communities still wanted to hear new music, especially the newest rhythm’n’blues tracks, but they had no way of accessing the records.

Fortunately, the records came to them.

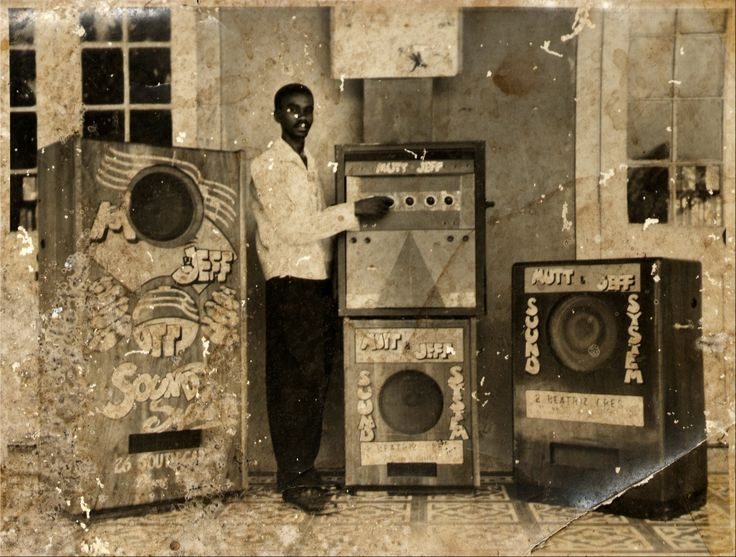

Sound systems started out as a kind of mobile disco. They were literally just some guy with a turntable and big speakers, who would set up in the middle of the street. People would gather round, dance, and generally have a good time.

These sound systems became an integral part of local culture, and soon rival systems were clashing with each other to dominate neighbourhoods. To win, you needed the best records, the best vibe; you needed to throw the best party.

Systems started getting creative. One technique was to have an MC who would talk between the records, in the style of American radio DJs. But these MCs began to develop their own vocal style, which was a more rhythmic, lyrical chanting.

Eventually, these vocal ad-libs evolved into the art of “toasting”—which is the technical term for Shaggy’s vocal style on ‘Oh Carolina’.

Sound systems evolved away from playing records and started creating more original beats. By the 70s, this style of music had two key elements: the riddim, which was the beat that got everyone dancing; and the toasting, which gave emerging stars a chance to shine.

Come the 1980s, and people started using technology to create new riddims on the cheap. In 1985, Wayne Smith and King Jammy got a Casio MT-40 keyboard, turned on the Rock preset, slowed down the tempo to 110 bpm, and used it as the riddim for their single ‘Under Mi Sleng Teng’.

‘Sleng Teng’ is considered the first big hit of a genre now known as dancehall. Dancehall is an offshoot of reggae, but with some key differences. Mainly, you don’t need a band to make dancehall. You just need a beat and an MC. Just two turntables and microphone.

Even before ‘Sleng Teng’, this was a powerful idea. And it was catching on outside of Jamaica.

3. Yuh just a rock to di riddim

The coolest place in 1970s New York wasn’t The Factory or Studio 54. It was Sedgwick Avenue in The Bronx, home to DJ Kool Herc’s parties known as Back To School Jams.

Herc is a Jamaican-born DJ who blew American minds by using sound system techniques, including chatting on the mic over records. The kids who attended his jams were also innovators, and they would take turns trying to improvise entirely new dance styles while he played.

Over time, Herc noticed that the dancing got especially crazy during drum solos and percussion-heavy sections. He started mixing his records to focus entirely on these drum breaks, chaining them together to create extended rhythms.

The kids went wild. They started moving in staccato, robotic movements to match the weird, futuristic drumbeats. Breakdancing was born here—and so was a new riddim that would become the backbone of 80s hip-hop.

Jamaican immigrants in UK enjoyed sound systems too, although most of these gatherings were illegal. Impresarios like Duke Vin organised parties in abandoned buildings or remote fields, where audiences danced to Jamaican records until the sun came up—or the cops arrested everyone.

(Fun fact about Duke Vin: he discovered that he was descended from a tribe that had signed a treaty with Britain in 1738. This treaty included a clause saying that the tribe were exempt from UK taxes. Vin successfully sued the Inland Revenue and had all of his income tax repaid to him.)

Essentially, British-Jamaican Dancehall fans were pioneering a version of rave culture at a time when white audiences were still listening to Showaddywaddy. When rave did become a thing in the 1980s, event organisers took inspiration from the old dancehall parties, and used the same techniques to evade the police. The music itself often collided: rave music + dancehall led to brand new genres, like jungle, drum’n’bass and garage.

So, dancehall played a vital part in shaping 90s music, even if most white audiences had never heard ‘Sleng Teng’. It makes perfect sense that reggae could succeed in the charts, especially if you combine it with hip-hop, r’n’b, or house.

Does that answer the original question?

Not quite. I still don’t understand one thing. Why now? Why 1993? Why is this the moment of the Reggae-naissance?

4. Prowl off, jump an prance

We haven’t yet discussed the biggest reggae song of the early 1990s.

This song was absolutely massive, so well-known that it was parodied in The Simpsons in 1992. Even people who hated reggae would sing along whenever they heard the chorus.

And they heard that chorus every week, during the opening credits of Cops.

Inner Circle recorded ‘Bad Boys’ in 1987—twenty years after they released their first album, and almost a decade after their first UK chart hit, 1979’s ‘Everything Is Great’.

When Cops started to become a global cultural phenomenon, their record label rushed out a new Inner Circle LP called Bad To The Bone. It seems likely that they were hoping to cash in on ‘Bad Boys’, so they were probably quite surprised when ‘Sweat (A La La La Long)’ became an even bigger hit.

My theory is this: an appetite for reggae had been brewing for some time. Partly because of ‘Bad Boys’; partly because of a renewed interest in Bob Marley (who charted with ‘Iron Lion Zion’ in 1992); partly because dancehall pairs really well with dance music and r’n’b.

But mainly because a lot of this music is really cool and fun and catchy.

Record labels had lots of reggae-adjacent acts, but they kept telling themselves, “nobody wants this music, reggae isn’t cool.” When they finally decided to give these acts a chance, mainstream audiences almost bit their hands off.

And so, you get a motley crew of reggae-flavoured hits all at once. Shabba Ranks re-releases “Mr Loverman” yet again? This time it’s a hit. UB40 puts a bit of skank on Elvis? Huge hit. Ace Of Base do their oddball scandi-reggae thing? Thanks, we’ll take a billion copies. Snow does… I don’t understand what was going on with Snow, but ‘Informer’ was also a big hit.

As for Shaggy, it’s easy to see why ‘Oh Carolina’ clicked. Shaggy’s whole persona is cheeky and slightly goofy, like a kind of Carribean Will Smith. His growling vocal style (inspired by the barking drill instructors from Shaggy’s military career) is both a piss-take of and an achingly sincere tribute to the old-school dancehall toasters.

That kind of ironic authenticity is just, like, so 90s.

The track is a pretty faithful cover of a 1958 record by the Folkes Brothers, which is itself a fascinating bit of music history—you can really hear American R’n’B evolving into island reggae.

Most of all, ‘Oh Carolina’ is just a fun record. That is the true spirit of dancehall, which has always been driven by a clear mission: to get everyone out dancing and having a good time.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.