Ride

‘Leave Them All Behind’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number 9 on February 9th, 1992

1992 was not a great year for music.

1993 will have some highlights. 1991 was incredible. But 1992 is a bin fire.

Yes, there are some high points, and eventually we will cover some landmark records like Automatic for the People and The Chronic. There were only twelve Number One singles in the whole of the year, and one of them was by Jimmy Nail.

1992 was a dreadful time for the music industry, with some of the lowest sales figures on record. This led to a major crisis behind the scenes, especially at the indie labels that had thrived in the 80s.

One indie label in particular found themselves at a crossroads in ‘92. This label was the engine behind a revolution in independent music. Their bands were critical darlings and commercial successes.

But the insane, drug-addled Scotsman behind the label was beginning to realise that none of this success mattered. Creation Records was in the same boat as every other indie label in 1992.

Financially, they were completely fucked.

In the early 1980s, the DIY punk scene had produced a number of British independent record labels, such Geoff Travers’ Rough Trade and Tony Wilson’s Factory Records.

These labels were boosted by a new wave of bands that would never have found a home at a major label. Factory signed Joy Division, Rough Trade signed The Smiths, Mute signed Depeche Mode, 4AD signed The Cocteau Twins.

Everyone was a winner. The bands made the records they wanted to make, and the labels made a profit.

Alan McGee moved from Glasgow to London in 1983, after the breakup of the punk band he had formed with his friends Bobby Gillespie and Andrew Innes (who would go on to form Primal Scream). McGee wasn’t much of a musician, but he had a nose for the business, and soon found himself working as a manager/promoter.

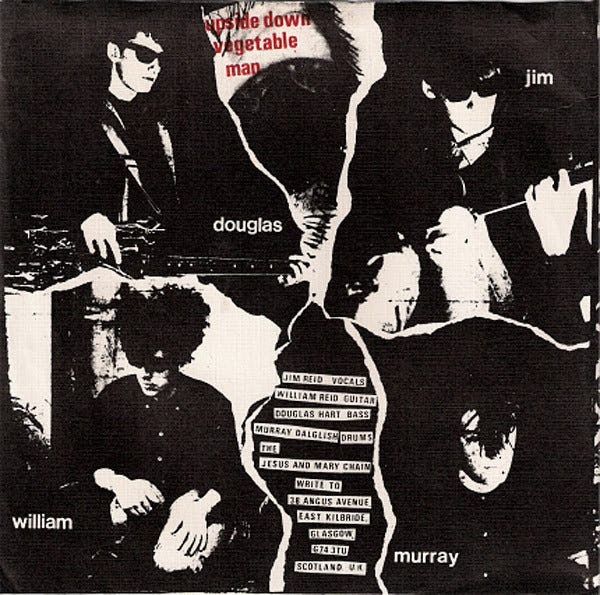

His first managerial clients were two brothers, Jim and William Reid. The Jesus and Mary Chain, as they called themselves, played fantastically chaotic gigs that typically ended in a riot.

(Rumours persist that McGee orchestrated these riots to get JAMC in the papers. If so, it worked. They were hailed as “the new Sex Pistols” purely because of the destruction they left in their wake.)

The first The Jesus and Mary Chain single, ‘Upside Down’, came out on Creation Records, back when Creation Records’ distribution network consisted of McGee hand-delivering boxes of 7”s to local music shops.

JAMC were snapped up by quasi-indie label Blanco y Negro, but they kept McGee on as manager. The money from this deal laid the foundation for Creation to become an increasingly serious presence throughout the late 80s.

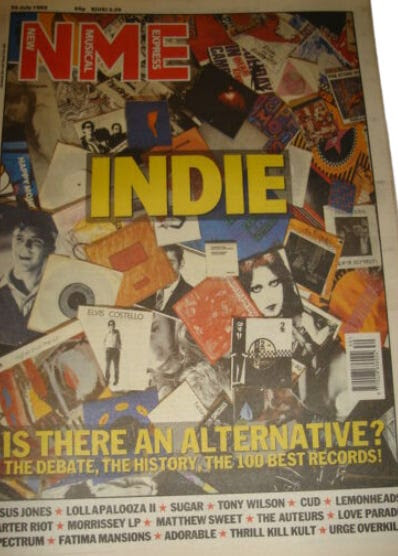

Fast forward to 1991, where the indie scene has never been bigger, and never been in more trouble.

Creation Records were the undisputed champs. McGee’s label had, in the space of a few months, released three of the greatest albums ever.

My Bloody Valentine had finally released Loveless, but only because McGee threatened to do terrible things if they didn’t hand it over. Kevin Shields of MBV describes McGee as a money-obsessed creep, but McGee tells it this way in his book, Creation Stories:

My Bloody Valentine’s progress was so slow it was killing us: 248 nights of recording took place during 1990 and 1991. I had to go and borrow money from my father – money from my mum’s life-insurance policy – to complete the album…Midway through 1991 Dick and I realized how truly and absolutely fucked we were for money. We needed three-quarters of a million quid to survive. My Bloody Valentine had fucked us.

Loveless was (and still is) a critical darling, but it would need to sell in Michael Jackson-level volumes to plug the hole it had created in Creation’s finances.

(Spoiler alert: it did not outsell Thriller.)

Then there was the surprise success of Bandwagonesque, the third record from Teenage Fanclub. Bandwagoneque was a surprise hit and went over amazingly well in the States, with people like Kurt Cobain championing Fanclub.

But instead of capitalizing on this success, Fanclub pulled back. McGee said:

With Teenage Fanclub, there was an element of self-sabotage in the way they went about their next album. It’s a Glasgow thing, of wanting to be cool rather than big.

And finally, there was Screamdelica. Bobby and Andrew from Primal Scream had started out in a band with McGee in Glasgow, and they had all come up on the London scene together, and now they had dropped their masterpiece on Alan’s label.

Screamdelica was a massive success, selling a ton of copies and winning the inaugural Mercury Music Prize. Behind the scenes, the Primals and the Creation staff were enjoying a never-ending party, fuelled by coke and heroin.

On the night that Screamadelica won the Mercury, the band’s manager lost both the award itself and the £25,000 of prize money that came with it. But who cares about money when you’re freebasing cocaine?

Creation’s success at the start of 1992 should have been a big deal, but it barely warrants a mention in McGee’s book. He simply says this:

The week after Primal Scream didn’t make the Top 10, Ride flew straight in at number 9 with ‘Leave Them All Behind’. Number 10 in the charts was ‘Reverence’ by the Jesus and Mary Chain. Primal Scream number 11. I had a royal flush of bands I’d signed! Tim and I celebrated with a four-day party.

(His book gives the impression that he didn’t really like Ride. Or, possibly, he liked their music but found the lads themselves a bit boring. Also, I don’t think McGee knows how to play poker.)

McGee had copied the Factory Records model of a 50-50 split with the band. Which is very honourable, but when you factor in the additional costs of recording, manufacturing, distributing and promoting — as well as the extraordinary amounts being spent on drugs and booze — Creation simply wasn’t turning a profit, regardless of how many records they sold.

Other indies were having the same problem. Rough Trade had declared bankruptcy in 1991. Factory Records would be gone by the end of 1992.

Everyone who ran an indie in 1992 seemed to face the same choice. Do we keep going and risk collapse, or do we sell out?

Alan McGee sold out.

In September, he signed over 49% of the company to Sony, which allowed him to pretend that he was still the boss. He wrote:

Sony bought 49 per cent of the company for £2.5 million in September 1992. The deal included an extra million to Creation to stop us from going bust immediately…Doing the deal with Sony mostly made us feel triumphant. We’d got through a situation that looked certain to crush us and we’d survived. But it was also the moment that Creation began to die.

Of course, this isn’t the last we’ll hear of McGee and Creation Records. As head of Sony-Creation, he signed one of the biggest acts of the 90s: Oasis.

But this is roughly the point where the DIY, post-punk indie explosion began to fade away.

But not yet. It’s still February 1992, indie still means independent, and Ride and Jesus and Mary Chain are both in the Top 10.

You won’t hear JAMC on Top of the Pops, because the BBC took exception to lyrics like “I wanna die just like JFK/I wanna die in the USA”. You won’t hear the full version of ‘Leave Them All Behind’ either because it’s eight minutes long and the first two minutes are a thunderous instrumental.

None of that matters. That’s the whole point of indie. You make the music first, and then worry about selling records later.