Paul McCartney

‘Hope Of Deliverance’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number 18 on January 17, 1993

1.

In 1993, Paul McCartney was living comfortably as pop’s elder statesman.

The late 80s saw him appear twice at Number One: first with a charity version of “Let It Be” for the 1987 Zeebrugge ferry disaster; and again with another charity single, “Ferry Cross The Mersey”, for the victims of Hillsborough in 1988.

Apart from that, he toured a lot, appeared on talk shows, promoted veganism, and occasionally put out pleasant little records like “Hope Of Deliverance”. And this was fine, because Paul McCartney had nothing left to prove by 1993. He had already changed the world.

This was the man who founded The Beatles. This was the man who wrote “Love Me Do”.

Or was he?

Some people weren’t so sure. Since the early 1970s, there had been murmurings about this man’s real identity.

And then, in 1993, McCartney released a record with what seemed like a very bland title. But truthseekers knew that this title was “Paul” thumbing his nose at thumb, boasting about the con job he’d been running for over 25 years.

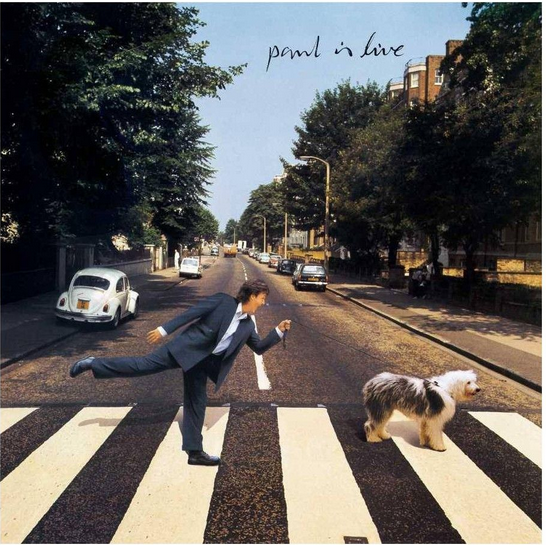

That album was called Paul Is Live.

2. I will understand, one day

You see, that’s not Paul McCartney on the cover. Because Paul is dead.

It’s okay if you weren’t aware of this. The lamestream media has brainwashed everyone into believing that Paul McCartney is “not dead” and “actually alive” and “clearly alive in that Get Back documentary” and “also very much alive when he headlined Glastonbury last year. ”

But that’s what they want you to believe. Here’s the truth.

On November 7th, 1966, The Beatles were locked in a studio, agonising over Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The pressure of Beatlemania had driven the Fab Four to the edge of sanity, and John and Paul were constantly screaming at each other.

While working on “She’s Leaving Home”, Lennon and McCartney got into a furious row. Paul walked out. Desperate to clear his head, he jumped in his sports car and went tearing down the M1 motorway.

It was a chilly winter’s night, and frost had made the roads treacherous. Paul, deep in thought, didn’t notice a green light turning to red. A skid, screeching brakes, and then… smash. The concussion rattled windows in nearby suburban homes.

Ambulances rushed to the scene, where they found a grizzly spectacle. The young driver had been decapitated by the sheer force of the impact. Paul McCartney was dead.

Any young death is tragic, but this seemed like a matter of national security. How would young Beatlemaniacs respond to such a loss? Would there be riots? Mass suicides? Would this create an opportunity for a Communist invasion?

Prime Minister Harold Wilson convened an emergency committee, and a plan was set in motion. The car crash—which had already been reported on local news—was embargoed under the Official Secrets Act. News reports were removed and eyewitnesses threatened with jail. A few weeks later, The Beatles announced a hastily-organised contest to find a Paul McCartney lookalike.

The winner was never announced.

But there was a winner—a Scottish orphan by the name of William Campbell. Campbell was whisked away in the dead of night. After a few weeks of make-up, plastic surgery and acting lessons, he was ready to pass himself off as the real Paul McCartney.

The surviving Beatles were furious about the deception, but they couldn’t speak out. Instead, they littered their records with clues and secret messages.

“A Day In The Life” explicitly tells the story (“He blew his mind out in a car/He hadn’t noticed that the lights had changed”.) The Sgt Pepper’s cover has a hand above Paul’s head—an Indian symbol of death. The Abbey Road cover is a funeral procession with Paul as a corpse—barefoot, as per Indian burial traditions.

Play “I’m So Tired” backwards, and you can clearly hear John singing, “Paul is dead, miss him, miss him…”

John explictly confirms the story in “Glass Onion” by singing:

“Well here’s another clue for you all

The walrus was Paul.”

“Walrus” comes from the Greek word ?????????, which means “corpse”.

3. And I wouldn’t mind knowing

Gosh, I almost convinced myself there.

Paul McCartney did not die in 1966, and is in fact still alive. The “Paul Is Dead” myth was propagated by bored American college students in the early 70s, who made a game of looking for clues in the Beatles’ back catalogue. When they couldn’t find a new clue, they just made shit up. For example, “walrus” comes from Norse, not Greek, and it literally means “horse whale”.

Urban myths and conspiracy theories can catch on, even when they’re obviously ridiculous and the “evidence” is garbage.

And I know this, because I accidentally started one.

Back in 2006, before “going viral” was a thing, I wrote a little humour piece for a website. It was a small, silly thing, intended for a small audience of my friends.

According to the thing I wrote, Pete Doherty of The Libertines is not a real person. He is, in fact, a complex art prank perpetrated by The KLF. Silly stuff, and obviously influenced by the Paul Is Dead thing.

Anyway, I posted this and immediately forgot about it. Then, a few days later, someone sent me a link to a music website that had repeated the story. Then another. Forum discussions started to pop up. People tried to add it to Doherty’s Wikipedia entry. Journalists started investigating. One website described it as “a complex hoax organised by a junkie-hating keyboard warrior.”

(It was not complex. I was just goofing around.)

The story fizzled out after a few weeks because it is so obviously untrue, and yet it still hasn’t vanished completely. In 2008, it was catalogued in a book of rock’n’roll legends (uncredited, mind you.) In 2021, someone dramatised the story in a podcast using proper actors:

My stupid Pete Doherty thing had nothing like the impact of Paul Is Dead, or any recent iterations of the story (such as the Avril Lavigne Is A Clone thing.) But it spread surprisingly far, especially consider that I put zero effort into the whole thing.

Imagine what would happen if someone was really trying?

4. The darkness that surrounds us

I first discovered the Paul Is Dead theory in a cheap paperback called something like World’s Weirdest Conspiracy Theories alongside all the usual greatest hits, like Nostradamus and the Kennedy Assassination.

Did it convince me that Paul McCartney was dead? Probably not, but I also didn’t really care. It was just a fun story and a neat thing to talk about with other people.

Perhaps this is the difference between an urban myth and a conspiracy theory. Myths are enjoyable; conspiracy theories make you afraid.

Unfortunately, our culture is leaning hard into conspiracy theories these days. Even something as delightfully goofy as Flat Earthism or The Mandela Effect can morph into furious yelling about how THEY are lying and YOU need to fight back.

This can get really ugly, like when conspiracy theorists dismiss tragedies by saying that the victims are “crisis actors”—phonies pretended to be real people, in the same way that an actor is supposedly playing Paul McCartney.

QAnon, an omni-conspiracy authored by far-right activists to help push a political agenda, tells believers that the world is run by a global cabal, and this cabal has left subtle clues all over the media. As a result, your deranged Facebook uncle has spent the last six years on an endless scavenger hunt, much like the students in the 70s who pored over Beatles LPs in search of hints about Paul’s supposed death.

5. We live in hope

How can we make conspiracy theories fun again? Is it even possible to spread folklore and amusing bullshit without threatening democracy?

I think it is, and I think the answer is to teach people how these myths work and why they spread so quickly. Paul Is Dead is a great case study because it’s such a charming little puzzle, with lots of clues and easter eggs you can follow. Even when you know its false, it’s still quite compelling.

Humans are pattern-seeking animals, and we get very excited when we spot a hidden pattern, like the arrangement of shapes on the Sgt Peppers’ cover. Putting the jigsaw together feels very satisfying.

But those patterns can also confuse us, causing us to lose sight of the big picture. The problem with the Paul Is Dead theory is… that’s very clearly the real Paul McCartney. Come on. He wrote hundreds of great songs after his supposed death, including “Penny Lane”, “Helter Skelter”, “Blackbird”, “Come Together”, “Get Back”, “Band On The Run”, “Jet”, and “Live And Let Die”.

Even something as pleasantly lightweight as “Hope Of Deliverance” is clearly from the same man that wrote “Love Me Do”.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

whvwwrnhquyyehyinvpjhrixuqhklt