Jimmy Nail

‘Ain’t No Doubt’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number One on July 12, 1992

Multiverses have become a common media trope in recent years. First, there was Rick and Morty, then the Spider-Verse, and now Marvel’s big spaghetti junction of colliding realities.

Perhaps the best of these stories of alternative realities is the recent A24 movie Everything Everywhere All At Once, starring an infinite number of Michelle Yeohs.

I don’t want to spoil this film if you haven’t seen it yet, but Yeoh plays multiple versions of the same character. Each one is someone (or something) she could have been if she’d made different decisions, or she’d been born in another environment.

This concept appeals to us because it asks something that’s always on our minds. How would life have been if you chose a different path? What lives could you have lived? Who else could you be? Are you the best possible version of you?

The French philosopher Henri Bergson wrote:

What makes hope such an intense pleasure is the fact that the future, which we dispose of to our liking, appears to us at the same time under a multitude of forms, equally attractive and equally possible. Even if the most coveted of these becomes realized, it will be necessary to give up the others, and we shall have lost a great deal.

Or to put it another way, the problem is that we choosing to take one path means choosing not to take another, and we are always haunted by those untravelled paths.

James Bradford was born in Newcastle in 1954. Like all kids, he dreamed thousands of possible futures for himself.

One dream was to follow in his dad’s footsteps and become a professional footballer. His father, James Bradford senior, had managed half a season with Huddersfield Town in the 30s, back when the Terriers were a big team.

He also really liked poetry and quite fancied being an English teacher.

But when Jimmy was 10, local band The Animals had a global smash hit with their cover of ‘The House of the Rising Sun’. From that moment on, Jimmy only wanted one thing: to be a rock star.

However, life took him in a different direction. He ended up in a rough-as-arseholes secondary school where teachers and students took turns beating the shit out of him. Some senior kids once threw him through a plate-glass window, giving him the first of five broken noses.

Jimmy decided that the only way to survive would be to become the hardest, maddest bastard in the school. He started fighting, and eventually got expelled for trying to burn the place down.

In the mid-70s, English football was going through its Mad Max phase. Jimmy joined a gang of Newcastle United-supporting hooligans and spent every weekend knocking lumps out of rival fans. He slugged a policeman during one fight, resulting in a six month stretch in Strangeways.

His dad came to visit him in prison and burst into tears, ashamed at what his son had become. This turned out to be one of those crucial nexus points where you think about your life’s path and choose an alternative direction.

After prison, he took a part-time job at a factory, where he managed to impale his foot on a six-inch spike. His sympathetic colleagues nicknamed him Jimmy Nail.

Bad decisions can lead us away from our dreams, but so can good decisions.

In his book Four Thousand Weeks, Oliver Burkeman says, “Every decision to use a portion of time on anything represents the sacrifice of all the other ways in which you could have spent that time, but didn’t.”

He goes on to quote Robert Goodin, who wrote a whole thesis on the idea of striving for a better life vs. settling for what you already have:

“You must settle, in a relatively enduring way, upon something that will be the object of your striving, in order for that striving to count as striving,” [Goodin] writes: you can’t become an ultrasuccessful lawyer or artist or politician without first ‘settling’ on law, or art, or politics, and therefore deciding to forgo the potential rewards of other careers. If you flit between them all, you’ll succeed in none of them.

In 1982, the BBC came to town looking to cast a new show set in the North-East. Although Jimmy had no interest in acting, his girlfriend bullied him into auditioning.

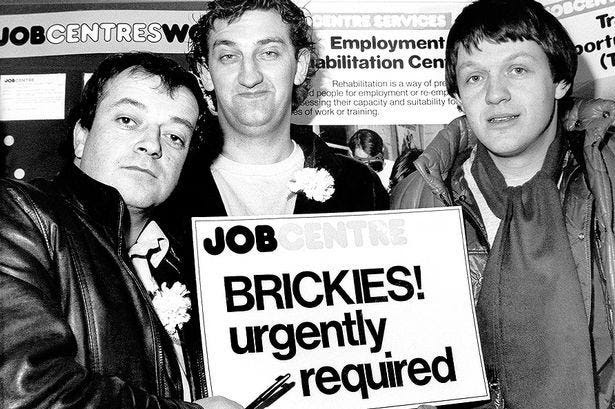

Imagine being that casting director. You’re looking for someone to play Oz, a psychotic, hard-nut brickie. In walks this guy who’s 6’ 3” and a face like a crashed lorry and who says his name is Nail.

They cast him on the spot.

Auf Wiedersehen Pet was a sensation, plugging perfectly into the zeitgeist of early Thatcherism. Jimmy Nail was now a famous actor, a legitimate star.

But he was still pushing to achieve his real dream of becoming a famous singer.

The world first heard Nail singing when Auf Weidersehen Pet allowed him to do a musical number as Oz. One of the other characters asked, “how can such a lovely voice come out of such an ugly face?”

In 1985, he managed a Top 10 hit under his own name with a cover of ‘Love Don’t Live Here Any More’.

It was fine, but it didn’t made him a rock star. He was just another bloke off telly who had put out a record, like Nick Berry or Dennis Waterman or Anita Dobson or Bruce Willis or Eddie Murphy or Glen Hoddle and Chris Waddle.

Shortly after, Auf Wiedersehen Pet went on hiatus, leaving him to ponder his next steps.

Where does the path lead next? Which version of Jimmy Nail will Jimmy Nail become?

Warren Buffet has this technique for organizing your priorities.

You make a list of the things you most want to achieve. Then you pick the main one, the thing that is most important to you, and you put all of your energy into that.

Most importantly—you stay the hell away from everything else on the list.

Every other item on that list is something that will split your focus. They’re things you’re interested in, but that you don’t really care about. It’s very easy to waste time and attention on those things.

At the start of the 90s, Jimmy Nail had his attention split between two goals: becoming a singer, and becoming a leading man.

It seemed like he would go down the latter path when BBC cast him in the title role of detective show Spender, which was a big hit and put him firmly in the spotlight.

Then, almost out of nowhere, he released ‘Ain’t No Doubt’.

‘Ain’t No Doubt’ (co-written by journeyman musician Guy Pratt, who also appears on this week’s Album Of The Week, U.F.Orb) is actually really good.

It’s a surprisingly complex number with three distinct sections, each of which succeeds in a different way:

Verse: Nail knows he’s not the world’s greatest singer (one of his later albums is called Ten Great Songs and an OK Voice). He leans into those limitations here by doing the verse as a spoken-word piece, which allows him to utilise his acting ability.

Bridge: Sylvia Mason-James does a smashing job on the female counter-vocal. Her lines swoop and soar with gorgeous dexterity before being shot down by Nail’s gruff “she’s lying”. It’s quite funny and the song’s most memorable bit.

Chorus: Don’t be distracted by the jazzy horns, this is actually a Full Metal Jacket-style military chant (“I don’t know but I been told…”), which is why it’s so catchy.

‘Ain’t No Doubt’ was more than just a hit record. It became the thing that defined Jimmy Nail’s career. It fundamentally changed the way we saw him. He is now, always and forever, Jimmy Nail: the singer who does a bit of acting.

But is he happy with this?

One of those parody news accounts recently did a gag about Nail doing an epic three-hour Glastonbury set

It’s entirely possible that Jimmy Nail lies in bed at night, wishing that this was his reality. He probably regrets the distractions that led him away from music. Maybe he even regrets his acting success. It brought him money and fame, but it distracted him from his true goal.

That’s the crushing thing about being alive, and the reason we love multiverse stories. No matter how successful or fulfilled we are, we live in the knowledge that we can only ever taste the thinnest sliver of what the world has to offer. We will always be outnumbered by the other versions of ourselves, the ones who never got a chance to live.

All of this means that true happiness is not about doggedly pursuing the optimal path in life. Instead, we must accept whichever branch of the multiverse we end up in, and try to feel at home.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!