Electronic

‘Disappointed’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number 6 on June 28, 1992

There are moments in life when you really, really need someone to come along and help you.

And sometimes, just occasionally, that person appears in your life out of nowhere. Almost as if the universe felt sorry for you and sent them your way.

Some years back, I was going through one of those life-altering breakups that was so bad I decided to move to another country. I booked a one-way ticket on a flight that was leaving in a week, and started packing.

Meanwhile, I downloaded an online dating app. I had no intention of meeting anyone, I just needed something to hide the fact that my phone had grown unbearably silent over the previous weeks.

A few days before take-off, I exchanged a couple of friendly messages with someone who lived nearby. She asked if I wanted to have a coffee.

I said that I was leaving forever in a week.

She said that coffee usually takes less than a week.

The next day, the two of us met. I started by saying, “I’ve just been through a horrible breakup”, which is how I started every conversation at that time. She said she had also been through a horrible breakup.

And the two of us—complete strangers—proceeded to spend the next four hours telling each other everything. Our entire life stories. The conversation moved fast because we rarely needed to understand anything. We both just understood.

We had each met the person we needed to meet in that precise moment. Almost as if they universe had felt sorry for us and sent us in each other’s way.

I found myself thinking about this while I was reading an interview with Johnny Marr about the path that led him to Electronic.

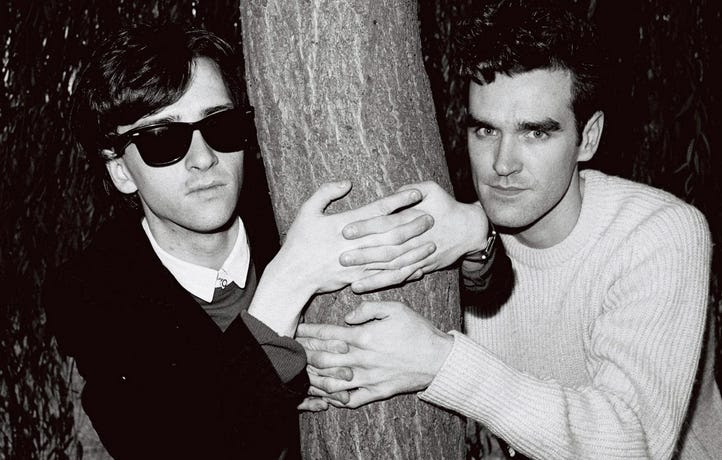

Marr is, of course, best known as the lead guitarist of The Smiths. That’s him playing the ground-shaking riff on ‘How Soon Is Now’. That’s also him playing the piano on ‘Asleep’, and the harmonica on ‘Ask’, and the marimba on ‘The Boy With The Thorn In His Side’.

Perhaps more importantly, Marr was the sole composer on all of The Smiths tracks. Morrissey may have created the line “And if a double-decker bus crashes into us/To die by your side is such a heavenly way to die”, but Marr injected it with the musical electricity that brought it to life.

This songwriting partnership started when Morrissey was 19 and Marr was just 14. Marr actually approached Moz—he just went round his house, knocked on his door, and said, “do you want to be in a band?”

The two bonded instantly and developed a rare song-writing chemistry. There’s a great interview where Marr talked about writing ‘Half A Person’, in which he says:

“[It was] the best songwriting moment me and Morrissey ever had. We were so close, practically touching. I could see him kind of willing me on, waiting to see what I was going to play. Then I could see him thinking, ‘That’s exactly where I was hoping you’d go.’ It was a fantastic shared moment.”

But the relationship imploded. By the time of Strangeways Here We Come, the two were barely on speaking terms.

Johnny quit The Smiths in 1987, but The Smiths weren’t finished with Johnny. Walking out of a generation-defining band isn’t easy, with fans and press both putting him under intense pressure.

Later, he found himself in court, defending the band’s profit-sharing arrangement that gave Morrissey and Marr 40% each, while Mike and Andy got 10%. The trial was a gruelling humiliation for all involved, and turned the already toxic Marr-Morrissey relationship into pure poison. The two are still having public spats in 2022.

During all of this, Marr tried to disappear into several other bands, first touring with The Pretenders and later recording with The The.

Both of those are great bands, but there was something tragic about one of England’s finest songwriters becoming, in essence, a session musician.

If the indie kids were upset when The Smith split up, imagine their response in 1980 when Ian Curtis killed himself.

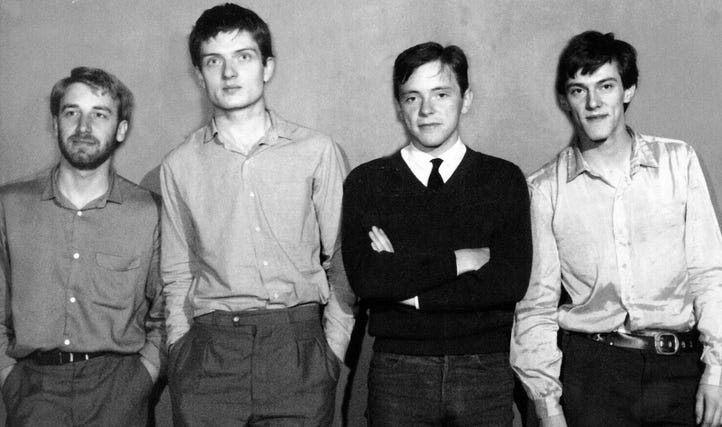

The music press stoked the mythmaking with Sounds Magazine’s infamous “He died for you” article. The surviving band members were left with only two options: split up and retire, or become a kind of Joy Division tribute band.

They did neither.

Instead, Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris (and Gillian Gilbert on keys) became a new band doing a new kind of music, with a more electronic, pop-oriented sound. New Order made songs you heard in clubs. New Order part-owned the most exciting club in Britain, Manchester’s The Hacienda, where ecstasy-fuelled rave culture was taking off.

Everything seemed great for New Order, but the band were increasingly strained as the 80s went on. The Hacienda was a money-losing, crime-ridden nightmare. Factory Records was run by a lunatic cokehead. Plus, Bernard, Peter and Stephen were still processing their survivor’s guilt after Ian’s death.

At the start of the 90s, New Order were entangled in their much-delayed album, Republic, which ran massively overbudget and wouldn’t reach record shops until 1993. By that point, Factory Records had collapsed. The Hacienda was hanging by a thread, as were New Order themselves.

Peter Hook said that by 1992, he and Sumner were “at that point in the relationship where you hate each others’ stinking guts”.

Let’s go back a few years.

It’s 1988. Bernard Sumner is touring America with New Order. Bernard hates touring America. Maybe it’s because Ian killed himself right before Joy Division’s U.S. tour; maybe he just hates America. Either way, Bernard is miserable.

Drugs have driven everyone in the band’s orbit a bit mad. There are money pressures. His relationship with Hooky is falling apart. And, although he might not know it yet, Bernard is a few months away from getting a divorce.

Bernard comes offstage in San Francisco, and there is Johnny Marr. Johnny is in Hollywood, experimenting with a career in movie soundtracks (which doesn’t pan out.) The two men are Manchester icons, but they barely know each other in person.

Bernard and Johnny talk, and find they have a lot in common. They start writing together and end up spending over 12 hours per day on collaboration. Bernard, now divorced, moves into Johnny’s house.

In an interview, Marr said:

When Bernard and I got together, initially, there was, of course, the musical agenda. We were excited about that. And I can look back now and say, well, there was a certain amount of us finding a bit of sanctuary from both having been in these intense Manchester groups. And we were getting to know each other, too, because we didn’t know each other that well on a personal level. But after that, we got to know each other very quick.

When asked why they get on so well together, he said:

“It was because Bernard and I both started out as guitar players in bands, not lead singers. So as successful and established a lead singer as Bernard Sumner is, he doesn’t have that wanker mentality – that has to hog the limelight all the time.

(Peter Hook might argue with the “Sumner is not a wanker” thing, but I’m sure we’ll tell his side of the story someday.)

The initial plan for Electronic was to release a few anonymous white labels. But it’s hard to stay anonymous when you’ve got a supergroup of this pedigree.

Neil Tennant begged to be involved and laid down some stunning vocals on their debut single, ‘Getting Away With It’, which was a surprise worldwide hit in 1989 (surprise in the sense that nobody was expecting a Marr/Sumner/Tennant collaboration).

Depeche Mode asked them to be their support act, so their first official gig together was in front of 70,000 people. And when the album finally appeared, Electronic received rave reviews from the music press.

Sumner and Marr will never be defined by Electronic. Nobody will ever introduce either them as “the guy who wrote ‘Get The Message’.” Although they released three very successful albums, it will always be a side project.

But for the two of them, it seems like an experience that changed their lives.

Marr said, “We lived in each other’s pockets for nine years…We worked together every day – 12 hours, 13 hours, every day, for years…we would go on holiday together.”

By all accounts, both of them really needed that kind of support, that kind of release at the time. It’s almost as if the universe took pity on them and sent them in each other’s direction.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.