David Essex

‘Stardust’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number 7 on January 12, 1975

1. The rock’n’roll clown

I’m currently reading War & Peace (flex) and I’ve only just picked up on one crucial detail: it’s set in the past.

Obviously, I realised that it wasn’t set in 2025—the presence of horses and lack of iPhones gave that away. But it took me a while to realise that Tolstoy was writing about a time before he was born, trying hard to bring history to life. It’s a period drama, like Bridgerton or That 70s Show.

Tolstoy was born in 1828 and wrote about the period leading up to 1812, which meant he was describing the world of his parents and grandparents. This is one of the most fascinating times for any of us to consider. The last few years of history without you in it, the time that grown-ups always call The Good Old Days, and about which they get annoyed when you call it long ago.

Of course, those of us born in the late 70s didn’t have to wait for a Tolstoy to tell us about life in The Good Old Days of early rock’n’roll. For as long as I can remember, the period between 1955 and 1970 has been eulogised, mythologised, and mourned like a lost Eden. My parents talked constantly about the music, the clothes, the incredible vibe of that period, as did almost every movie and TV show ever made since.

Boomer nostalgia didn’t even take that long to emerge. By the early 70s, the US was reminiscing over the rock’n’roll era with things like Happy Days and American Graffiti. Meanwhile, in the US, Ringo Starr himself appeared alongside David Essex in an ode to the era called That’ll Be The Day.

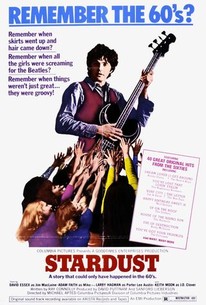

That’ll Be The Day was so successful that it inspired a rush sequel called Stardust, which appeared in 1974. The poster for Stardust reads like this:

REMEMBER THE 60’s?

Remember when skirts went up and hair came down?

Remember when all the girls were screaming for the Beatles?

Remember when things weren’t just great… they were groovy!

STARDUST

A story that could have only happened in the 60s

This was only a few years after the decade ended—people still had tins of beans in their cupboards that were canned in the 60s. And yet, the Boomers already wanted to hear their story retold.

So, what story did they tell themselves?

2. Roll on up, won’t you come and take a look at me

(This contains spoilers for both movies. They’re both episodic rather than plot-driven, so spoilers shouldn’t ruin your enjoyment. Also, they came out in the 70s. You’ve had 50 years to watch them.)

The first film, That’ll Be The Day, starts with a small boy being woken in the middle of the night. His mother puts a Union Jack in his hand and tells him to go say hello to his daddy. The boy runs onto the street where he sees a shadowy figure approaching—his father, presumably returning from the war. Cut to a few years later, and the father tells the boy, “I tried to settle down again”, before vanishing, leaving the boy to be raised alone by his mother.

This opening scene explains everything that happens in both movies. Growing up without a father is a deep psychic wound. It leaves our protagonist, Jim Maclaine (played by David Essex), without a moral compass or a role model to whom he can aspire.

This psychic wound was common among lots of boys born in the 1940s, even those whose fathers didn’t die in the war. John Lennon, born in 1940, grew up without a dad around. His friend, the Canadian songwriter Harry Nilsson, wrote a song called ‘1941’ about his own childhood experience:

Well in 1941, a happy father had a son

And by 1944 the father walked right out the door

And in ’45, the mom and son were still alive

But who could tell in ’46 if the two were to survive?

The rest of the lyrics tell the story of a young man growing up, rudderless and lost. He works at a carnival for a while, then has a wife and son of his own, before abandoning both in favour of life on the road.

Many people identified with the lyrics of ‘1941’, including a young advertising executive named David Puttnam. Puttnam was breaking into the world of movie production and had just enjoyed a hit with his first project, Melody, a teen romcom featuring the stars of Oliver! Although Puttnam’s own father had returned safely from the war, many others had not. When that fatherless generation became teenagers, it led to the recklessness and excitement of the 1950s. Puttnam approached screenwriter Ray Connolly (whose father had been killed in the war) and the two began working on a movie loosely based on ‘1941’.

Both men were especially excited about making a film set in the early rock’n’roll era as it meant they could include their favourite tunes. Puttnam had the genius idea of approaching Ronco for investment. Ronco was an American kitchenware company that owned a subsidiary called Ronco Records. Like their main rival, K-Tel, Ronco Records specialised in tacky compilation albums which they advertised with equally tacky TV adverts. Puttnam asked if they would like to collaborate on a soundtrack and, perhaps, invest in the film?

Ronco didn’t want to invest in the production, but they pitched a different idea: they would produce a tie-in soundtrack and spend £300,000 on TV advertising, essentially giving That’ll Be The Day a Hollywood blockbuster level of marketing. With that kind of support in his pocket, Puttnam had no issues finding backers to finance the film.

But there was catch: Ronco wanted to release a double LP, which meant that Puttnam had to wedge at least 40 songs in the finished movie. This involved several rewrites and turned That’ll Be The Day into something of a jukebox musical, with dozens of 50s hits stuffed into its 90-minute runtime.

And that’s not the only thing it was stuffed with. That’ll Be The Day was also going to feature a lot of sex.

3. See my painted-on grin as a stand up to sing

“Week by week we would then ransack our own lives as we created the fictional character of Jim Maclaine. After about three months I had a first draft of the script. Unfortunately, however, the Jim Maclaine character hardly did a decent thing in the entire story. He was the ultimate selfish teenager.

“We needed something to make him likeable.”

Sex in England was invented in 1963, according to poet Philip Larkin (“Between the end of the Chatterley ban/And the Beatles’ first LP”). British cinema-goers might have felt it was invented even later, due the the BBFC’s stringent film classification rules. Up until 1969, films were either rated U for Universal or A for Adult (the modern equivalent of PG). Everything else was rated X and only available to people over 16, if those people could even find a cinema showing X-rated movies.

But movie-makers kept pushing boundaries in the 60s. The BBFC relented in 1970 and introduced a new rating tier, AA, which allowed some adult content as long as viewers were over 14. Suddenly, the chaste world of teen flicks were filled with more swearing, violence, and erotic sights such as Ringo Starr’s left arsecheek, which has a cameo appearance in That’ll Be The Day.

Ringo (and his buttock) were cast almost by accident. Screenwriter Ray Connelly had no experience of Butlins-style holiday camps in the 1950s, but he did know Ringo Starr, and Starr had famously been in a band that played a residency at Butlins (he was still gigging there when The Beatles recruited him to replace Pete Best.) Ringo told Connelly all about his dubious exploits during the Butlins era, and eventually it was suggested that he play the role of Mike, a lascivious and chauvinist ex-Teddy Boy now working as a Butlins redcoat.

(Ringo played in a band called Rory Storm & The Hurricanes. That’ll Be The Day’s features a similar band called Stormy Tempest and the Typhoons, with 50s rock’n’roll legend Billy Fury on vocals and Keith Moon on drums.)

Mike/Ringo’s role in the film is to lure the protagonist, Jim, into a life of lust and womanising. Jim is played by David Essex, who was coming off a successful West End run of Godspell in which he played Jesus (so it wasn’t too hard for him to play another young man with daddy issues.) Essex gives Jim a twinkly-eyed, naive charm. As Connelly later said, Essex’s charisma would be essential, because Jim is a horrible character.

After Mike helps him lose his virginity (to Doctor Who‘s Deborah Watling), Jim becomes a relentless womaniser, pursuing anything in a skirt. This is all light-hearted titilation at first, but soon becomes a study of moral decline. We see Jim assault a schoolgirl in pretty horrifying fashion. He goes home with a girl, then slaps her because she has a baby. He seduces his childhood best friend’s fiancee. Even Mike tells him he’s gone too far, and you know you’ve messed up when Ringo Starr is angry at you.

The moral of the story is: the 50s were fun but at a price. While everyone was enjoying Elvis and jiving, society was crumbling, and it may be too late to go back. That’ll Be The Day ends the same way as Harry Nilsson’s song: Jim has a wife and child, but abandons them both. The final scene shows him buying a guitar and heading off in pursuit of a new life in rock’n’roll.

4. Hey rock’n’roll king is down

That’ll Be The Day was an enormous success—especially for Ronco Records, as the soundtrack LP spent seven weeks at the top of the album chart. David Essex’s solo musical career was also taking off, and Puttnam decided to strike while the iron was hot. A sequel went straight into production.

Stardust picks up right where That’ll Be The Day left off. Jim is now in a band called The Stray Cats (not to be confused with the actual Stray Cats, who brought Rockabilly into the 80s) who play Beatles-ey pop songs in a venue that looks suspiciously like The Cavern.

It’s an interesting historical moment, this, the quiet period in the 60s between Elvis and The Beatles. For a moment, it looked like rock’n’roll might be a fad that had already burnt out. A lot of early British rock’n’rollers (such as Billy Fury, who appeared in the previous movie) fell by the wayside in the early 60s as the genre waned. At the beginning of Stardust, it seems like The Stray Cats are headed for the same fate and Jim has thrown his life away for nothing.

But Jim thinks The Stray Cats just need a good manager to help them chart a path to success. He reaches out to his old pal Mike, who turns out to be an excellent manager. After relentless touring around the country in a rickety van, Mike helps the band sign a record deal with a big label.

Now, while Mike is the same character from That’ll Be The Day, Ringo Starr didn’t return. Instead, the role is played by Adam Faith, one of the biggest stars of the pre-Beatles British rock’n’roll era. Faith is an incredible piece of casting, as handsome as any Hollywood star but with a palpable sense of inner turmoil. There’s a scene early on where The Stray Cats are recording their first single. As Jim lays down the lead vocal, Mike stares daggers at him, clearly thinking, “It should be me down there”. You can’t help but wonder how much of it is acting and how much is Adam Faith, the person, looking at David Essex and having the same thought.

The song is a hit, and Britain succumbs to Stray Cats-mania. Jim is having threesomes with models (in a scene that really pushes the AA rating to its limit) and loving the rockstar life. When the band lead a British invasion of America, Jim is on top of the world. Which means there’s nowhere to go but down.

Jim is slowly consumed by money, drugs and ego, eventually splitting from The Stray Cats and going solo. This frees him up to work on his opus: a prog-rock epic celebrating women, which he performs on live TV in a worldwide broadcast. It turns out to be a spectacular hit, despite the fact that (a) it’s terrible, (b) Jim is a raging misogynist, and (c) Jim’s Yoko-esque girlfriend, really the only female character in the movie, has left him after she discovered him and Mike partying with hookers.

Up to this point, Stardust’s history of the 60s goes something like this: 1960-62 were pretty good; 1963-66 were the greatest time to be alive; 1967 onwards was a slow descent into hell. Even then, the film still questions whether the early 60s were all that great. Late in the film, Jim asks Mike, “We had a lot of fun back then, driving around in the van, didn’t we?” Mike looks at him coolly and says, “No”.

Stardust’s final act begins around 1970, which means it’s stopped being a period drama and is now set in the present day. We’re looking at the legacy of the 60s, and Stardust does not like what it finds. Jim is unthinkably rich and famous, but he’s been abandoned by everyone except Mike. The two have a co-dependent relationship which may or may not be sexual.

Jim’s tired of it all, so he buys a huge castle in Spain where he intends to make music, but mostly just takes drugs and withers away. There’s a scene where he gives LSD to a pregnant dog, causing the dog to miscarry. This leads to a tableau that seems to sum up the movie’s feelings about the 1970s: beloved 50s pop icon Adam Faith is on his knees, covered in aborted puppy blood, while beloved 70s pop star David Essex says, “Just a bad trip really, eh?”

The Jim Maclaine story ends when he’s pressured to return to the spotlight by his American manager (played by a pre-Dallas Larry Hagman, although his character is essentially J.R.) Jim agrees to a live televised interview from his castle. But he takes a lethal amount of heroin right before cameras roll and dies on live TV. The last scene of the movie is dozens of paparazzi scrambling to get a picture of his corpse, while Adam Faith screams, “It’s a good story, innit?”

And that was the 1960s. A good story with a bloody ending.

5. In a stardust fling

Nostalgia is never really about the past. It’s about right now.

Tolstoy wrote about 1812, but he was talking about the 1860s, about how (his) modern Russia came to be. That’ll Be The Day and Stardust are both really about Britain in the 1970s, a time of unrest and unemployment, a general feeling of inexorable decline. Both films search for the point where things went wrong. Was it the drugs? Was it the sex? Was it the music? Was it all America’s fault? Was it all those boys growing up without fathers?

Right now, in 2025, the Bob Dylan film A Complete Unknown is in cinemas. It focuses entirely on his early career, that febrile moment in the early 60s when he could have been anything. When the world could have been anything. When we could have built paradise here on Earth if only we’d made the right choices.

Maybe it’s because I’m Gen X, but I don’t think that’s true that history pivoted on the events of 1962. I think a cohort of people were young in 1962 and found life very exciting, and life was never again quite as exciting for them. It happens to us all, but that particular cohort had an unusual degree of control over the stories we tell ourselves, and so their story has become the dominant version of history.

That’ll Be The Day and Stardust are among the first drafts of that history.

Thanks for reading! Join the Patreon to read about the prog-rock legend who should be mentioned above, but isn’t. Also, a look at the Top 40 from this week in 1975. Here’s the link!.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

Fascinating stuff.

I should point out, though, that Harry Nilsson was actually American.

Enjoyable read! I watched both films during the first covid lockdown.

Nostalgia is a funny thing: the passing of time plays tricks on our minds – people were even nostalgic for WW1 – and the usual temptation is to just remember the “good times”. I quite like the way both films don’t fall into that trap.

Excellent piece, thank you.

I was born in the early 70s and through late night showings on UK television in the 80s, both films quickly became favourites of mine…for obvious reasons for a teenage boy (the ménage à trois in Stardust had my eyes out in stalks) but having viewed the recent DVD reissues of both films, they really are very, very good films in their own right.

And you’ve taught me something I didn’t know about the attempted Ronco funding. I do have both soundtrack LPs, picked up from charity shops.

I think they’re both overlooked in favour of Slade In Flame. The difference being with the two David Essex films is that they both feature people who can act.

Thank you. A really enjoyable read.

mnuh0y

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.