Beck, ‘Loser’

Song facts

Released: Month 8, 1993

Highest UK chart position: #15 on March 6, 1994

1. In the time of chimpanzees I was a monkey

If you’ve ever picked up a guitar and tried to strum a Dylan song, you’ve probably daydreamed about making it on the New York folk scene.

Imagine it. You arrive in Greenwich Village with nothing but the shirt on your back. You go to an open mic night in a cool cafe, and you start to play. Everyone stops talking. Someone in the front row starts crying. Joan Baez is there; she says you’re the best singer she’s heard since Nixon was president.

People really do go to New York with nothing but a guitar and a dream, hoping to make it on the folk scene. In 1989, one hopeful took a cross-country bus from L.A. to the Big Apple, armed with exactly $8 in cash and a firm belief that he could be the next Woodie Guthrie.

He lasted two years. By 1991, after being beaten up, robbed, left homeless, and rejected by the folk scene, he slinked back to California

But New York hadn’t been a total bust for Beck Hansen. During his time there, he had discovered an underground scene that changed the way he thought about music.

2. I’m out to cut the junkie

Earlier in the 1980s, another aspiring performer had tried and failed to break into the New York folk scene.

Lach, a native New Yorker, loved folk and punk music in equal measure, and he wanted to merge the two into something new. He decided to try airing some of his compositions at Folk City, the venue where Bob Dylan played his first real gig.

Folk City did not enjoy Lach’s music:

Well, I was banging on the piano like it was the Ramones, and a couple of people were like, “that’s really cool”’, but a lot of people were like, “what the hell was that?” The next people would come up and play something like a Woody Guthrie song or whatever they were calling folk at the time; bland, white boy, college educated and boring.

From: https://www.antifolk.com/lach-interview/

All of the other folk venues felt the same way. Rather than give up, Lach decided to try opening his own venue. The Fort was a place where everyone was welcome to try out ideas that didn’t fit in places like Folk City.

The week we opened The Fort, they had the New York Folk Festival in the West Village. I didn’t consider anyone on that bill to be an actual folk artist. To me folk music is traditional music, old Irish, Japanese, Jewish music, you know. But this was all white guys and good looking white chicks, playing acoustic guitars singing their diary entries over 3 or 4 chords. Nobody was making any waves.

If they were going to call that ‘folk music’, we were going to call what we were doing ‘antifolk music’. So then I held an antifolk night at The Fort, we had the first Antifolk Festival.

https://www.antifolk.com/lach-interview/

The Fort started to take off, becoming a home to experimenters and eccentrics. And then, some of those acts started getting signed. Kirk Kelly, who launched the antifolk movement with Lach, released a record on SST. Cindy Lee signed to Rhino Records. Michelle Shocked went mainstream and had an international hit single.

Antifolk was starting to have a moment.

3. Kill the headlights and put it in neutral

New York wasn’t the only place where outsider artists were dominating the folk scene.

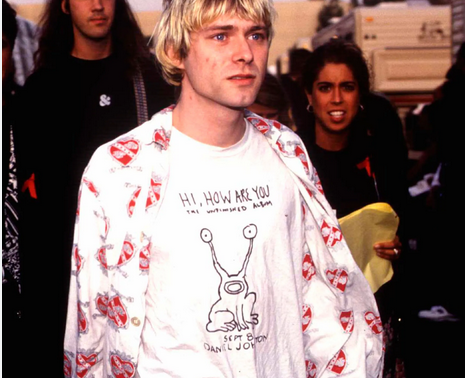

Down in Texas, Daniel Johnston had earned a cult following for his weird, primitivist songs that he recorded at home on a cassette deck. Kurt Cobain wore a Johnston t-shirt around the time of Nevermind, which helped propel the lo-fi icon into the mainstream (or, at least, the upper reaches of the underground scene).

Johnston had mentored a young singer-songwriter known as Paleface, who later moved to New York and became one of the brightest lights in the antifolk scene. Paleface seemed to be going places—Danny Fields, former manager of The Doors, had signed him as a client and a record deal was on the way.

Paleface believed in antifolk’s pay-it-forward ethos, so he took an interest in one of the kids who was trying to break into the scene. A 2017 New Statesman feature on Beck tells the story of what happened next:

At the time, Beck was infiltrating New York’s “anti-folk” scene, the wave of ’80s acoustic musicians who’d grown up on punk, liked to scream, and were out of place in the more traditional folk joints, establishing themselves instead in the bars of the Lower East Side. For a while, he lived with Paleface, a lo-fi lynchpin of the movement who’d learned songwriting from the reclusive Daniel Johnston. Beck has claimed a debt to the celebrated ingénue with his blond hair and baby features, but Paleface is hard to track down, given – as his drummer girlfriend explains – that he has no mobile phone, no social media accounts and is only just learning to use a computer. Eventually, an email arrives:

I first saw beck on the streets of ny city with a guitar slung over his shoulder peering in the window of some club… i thought 2 myself this guy looks cool so I went right up 2 him. i asked him 2 play somethin, forget what it was but yes I knew within seconds this guy was gonna do somethin. it wasn’t that he was all that great but he just had it.

Beck had a flair for stage performance, which he possibly inherited from his mother, Bibbe Hansen, who had been an actress and a face at Andy Warhol’s Factory. However, Beck’s music was dull, relying too heavily on old folk standards.

Eventually, Lach decided to offer some guidance:

“[Beck] was mostly doing cover songs then, Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie and stuff like that,” says Lach, songwriter and founder of the Antifolk movement. “My impression was that he was a sweet kid who was far from home, and that he needed to write songs. I remember telling him, ‘You gotta write,’ and he said something like, ‘Well, what do you write songs about?’ I said ‘whatever you feel, whatever’s going on in front of you. If a weird looking dog walks by, and you’re hungry for pizza, write a song about that. Just make it you.’”

https://americansongwriter.com/beck-to-the-future/

Beck was becoming more comfortable in antifolk, but having a less happy time as a New York resident. He spent years sofa-surfing while saving for a deposit on an apartment. Someone found his savings (all $600 of it) and decided that he was a phony rich kid. Nobody would let him sleep on their sofa anymore.

When he tried getting an apartment, he got scammed. A woman posed as a landlord, took his $600, and said she’d come right back with the keys. He never saw her again. Not long after, he got jumped by a gang on Alphabet Street, leaving him in hospital with a brain injury.

By the end of 1991, Beck had enough. He went back to California and started working in a video store, his dreams of stardom crushed.

4. Soy un perdedor

Beck kept performing, although his gonzo antifolk energy wasn’t hugely successful. Nobody would give him a gig, but some bands would let him play a few songs to baffled crowds while they got set up.

(A typical Beck gig at the time involved him dumping a bag of dead leaves on the stage, then clearing them off with a leaf blower. You can see some footage of that in the ‘Loser’ video.)

In 1993, Beck met hip-hop producer Carl Stephenson. The two agreed to do some folk/hip-hop experiments, with Stephenson producing a slide-guitar powered beat. Beck started rapping, throwing out stream-of-consciousness phrases, many of which were inspired by his disasterous time in New York.

Beck felt that the finished track was mediocre, but Tom Rothrock, head of Bong Load Records, insisted on releasing it as a single. 500 copies of ‘Loser’ were pressed. The song soon spread like wildfire, jumping from college radio to rock radio to commerical radio. Geffen Records snapped up Beck, and ‘Loser’ became globally recognised as the national anthem of Slacker culture.

5. Choking on the splinters

The New York antifolk scene kept producing acts after Beck: The Moldy Peaches, Regina Spektor and Jeffrey Lewis all started there. Lach eventually moved to the UK (he’s still making his own music, which you can get on Bandcamp).

These days, music scenes like antifolk are becoming increasingly rare. Venues are shutting down, live music is in crisis, and artists simply can’t afford to live in cities. Rents in New York have increased 800% in 30 years—you simply can’t exist there without a steady income or help from family.

And yeah, artists have other options now. You can find an audience on YouTube or TikTok, and there are no gatekeepers telling you what you can or can’t do.

But what’s lost is community. Artists need help from other artists. When artists have space to be together, to dick around, to share advice and critique each other’s work… you end up with results like ‘Loser’.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

yhspzh

lxpsm6

ohtosa

xjudg9