Annie Lennox

‘Love Song for a Vampire’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

#3 on February 13, 1993

In the summer of 1725, a small Serbian village near the Danube was rocked by a series of mysterious deaths.

The first to die was a local named Petar Blagojevi?. This death was sudden, but not unusual by the harsh standards of life in 18th-century Serbia. Blagojevi? was buried in accordance with local customs, and his grieving widow began her mourning period.

A few days later, another villager died violently in their bed, seemingly murdered. Another victim followed, then another. One victim survived long enough to name the assailant who had attacked them in their bedroom .

It was Petar Blagojevi?.

His widow refused to believe the anxious murmurs about her dead husband, until one night, when she was disturbed by a dull, heavy, pounding on her door. It was her husband, Petar, looking as alive as ever, although his eyes were now black, and his skin a ghastly grey.

“Give me my shoes, woman,” he growled at her.

The widow ran as fast as she could, never again returning to the village. Blagojevi? continued his rampage, killing nine people in a single week.

The villagers demanded official help, and an inspector named Frombold was sent to investigate. With some help from a priest, Frombold exhumed Blagojevi?’s corpse, which seemed to be in a remarkably fresh state. More remarkable still, the corpse’s mouth was filled with fresh blood.

Local folklore was filled with tales of Back-From-The-Dead creatures like this one. Folklore also explained how to get rid of them. The villagers staked Blagojevi? in the heart, decapitated him, cremated him, and finally scattered his ashes on running water.

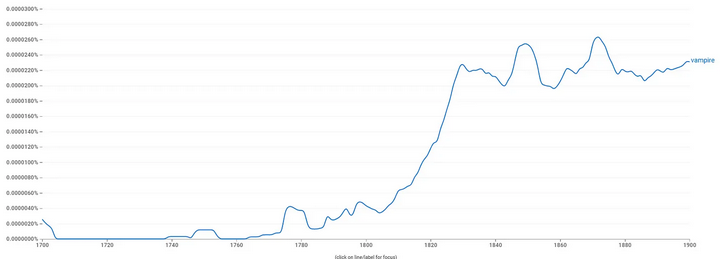

Frombold filed an official report, in which he used the same word that the villagers had used to describe Back-From-The-Dead demons, a word that had never appeared in print before: vampyri.

Early 18th-century newspapers loved a bit of sensationalism. They reported on the Petar Blagojevi? incident and similar supernatural panics across Europe. Soon, vampires became big business.

The rhythm of this trembling heart

Pop culture vampires went through many iterations during the next 300 years, although many of them contain some element of this first story.

The first big hits of Vamp-Lit were German narrative poems, like Lenore and Goethe’s The Bride of Corinth, both of which focus on people who, like Blagojevi?, rise from the dead to reunite with their lovers.

Moving into the 19th century, you get the Penny Dreadful blockbuster, Varney The Vampire, which leans into the terror of the original folklore. Varney is not just a monster—he’s a conniver who lures his victims to their deaths, which makes him a compelling antagonist.

In 1872, Irish author Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu created a new kind of vampire in his novel Carmilla. Carmilla is a beautiful seductress who preys on young women—a very daring bit of LGBT representation that also highlights the transgressive sexuality at the heart of the vampire myth.

Vampire stories were almost 200 years old when Bram Stoker published his 1897 novel, Dracula. Yet this soon became the definitive version, thanks to the way Stoker deftly combined so many elements of the vampire mythos. Most importantly, he understood that vampires are equal parts scary and sexy. Dracula is a murderous demon, but he’s also exotic and electrifyingly charismatic, and it’s not always clear whether he’s motivated by hunger or by lust.

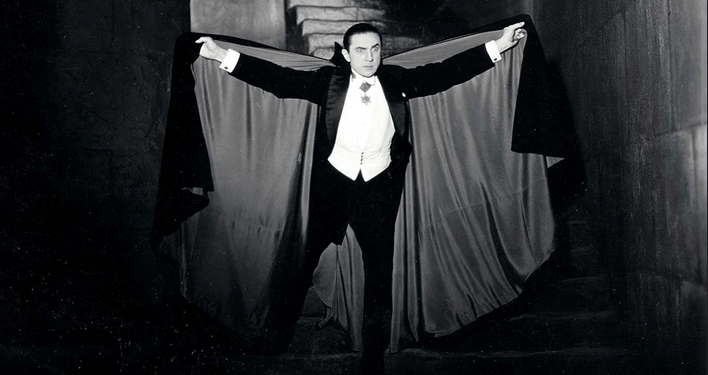

Bela Lugosi’s portrayal of Dracula in the 1931 movie captured the scary and sexy elements of the character while introducing something new: camp. There’s a fundamental silliness to this version, a combination of Lugosi’s thick accent, slightly hammy performance, and his distractingly fabulous cape.

Movie vampires have never really been scary. Instead, they’ve gradually become slightly silly. When Bela Lugosi reprised his Dracula role in the confusingly titled Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein, it actually seemed a like good fit for the character. Vampires were now a Halloween costume, a silly accent, a string of dumb catchphrases like “I vant to suck your blood, blah!” Before long, vampires were being used as cereal mascots, while a vampire puppet taught kids how to count.

The late 20th century produced some fine vampiric horrors (Near Dark, The Hunger, some of the Hammer Dracula movies), but vampires found a new home in the growing genre of horror comedy. The 80s produced Love At First Bite, Monster Squad, Vampire’s Kiss, Fright Night, and one of the most commercially successful vampire movies ever, The Lost Boys.

Vampires were kind of goofy now, but there’s also an element of goofiness in the Petar Blagojevi? story. Remember, Blagojevi?’s main gripe was that he didn’t have any shoes, and the villagers decided to seek an official a Certificate of Vampiricism from the government before staking him. That’s all pretty funny.

It beats for you, it bleeds for you

The 90s had this weird air of cultural superiority. Previous generations were morons, especially those idiots in the 1980s. We were much smarter and more self-aware, and we had read several books on post-modernism.

The 90s also had this post-grunge obsession with authenticity. We wanted to shrug off the plastic artifice of the previous decade, and nourish ourselves with something that felt real, man.

It was an era of gritty reboots, and it was inevitable that someone would eventually try to reboot Dracula.

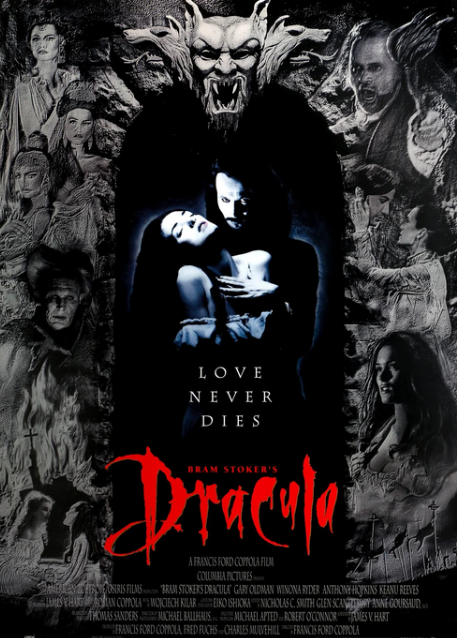

In fairness, Francis Ford Coppola seemed like the right man. His two greatest movies—The Godfather and Apocalypse Now—were both adaptations of novels, and some would say that his films were better than the original texts.

Just to ram home the point, his movie was called Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which implied that he was drawing directly from the original text and ignoring all previous adaptations.

Hopes were high. An all-star cast was assembled, featuring Gary Oldman as Dracula, Winona Ryder as Mina, Anthony Hopkins as Van Helsing, and Keanu Reeves as someone struggling to do a British accent. Everyone was excited for what promised to be a brand-new look at vampires.

When the movie appeared, it was… fine. Rotten Tomatoes gives it it 77%, which seems about right. It’s very entertaining, it looks amazing, and it has some clever ideas. The main flaw, besides Keanu, is that it’s not as faithful as had been promised. For instance, Coppola added a love story about Mina being the reincarnation of Dracula’s wife, which ties into earlier vampire stories but is not part of Bram Stoker’s novel.

Also, it’s still quite silly. Gary Oldman gets some bizarre fits, such as the double-bun look and his ridiculous 90s sunglasses.

Maybe there’s no way to tell a vampire story without being slightly daft. Maybe vampires are always little scary, a little sexy, and a little silly.

Or maybe we’re looking at them wrong.

Come into these arms again and set this spirit free

When Annie Lennox was approached for the Dracula soundtrack, she had little interest in Bram Stoker’s book.

Instead, she’d grown fond of a new series of novels: The Vampire Chronicles, by Anne Rice. Rice published the first installment, Interview With The Vampire, in 1978, then created a sequel with George RR Martin-like speed: 1985’s The Vampire Lestat.

Rice was one of the first authors to successfully ask the question: what’s it like to be a vampire? Her characters, especially the wonderful Lestat, show that it’s sometimes good but mostly awful. You’re alone, outcast, damned to never again be part of the world. You have no one in your life except other vampires, which means that you become part of a dysfunctional, co-dependent pseudo-family. Rice’s novels struck a chord with Lennox, who recognised the themes of addiction, including addiction to toxic people.

Lennox and Rice were also united in tragedy. Rice’s daughter Michele died of leukemia at age six, right before she began writing Interview With The Vampire. In 1988, Lennox’s son Daniel was stillborn, a trauma that later drove Annie to become a campaigner for women’s healthcare.

Grief is the strongest emotion for Rice’s vampires. Many of her characters became vampires because they were fleeing from grief, or because they hoped to save a loved one. But vampirism couldn’t protect them from tragedy—it merely condemned them to live in their grief for a few extra centuries.

This emotion is the tender heart of “Love Song for a Vampire”. It’s a vulnerable song about loss, and the feeling of a grief that might go on forever.

Rice’s vampires ultimately saved the genre. Her new approach added depth to Buffy The Vampire Slayer, inspired the millennial silliness of Twilight, and was ripped off pretty much wholesale in things like True Blood and The Vampire Diaries.

Personally, I’m a big fan of Shadow Of The Vampire, a 2000 movie that asks the question: “what if Max Shrek in Nosferatu was a real vampire?” There’s a great scene where the vampire says he has read Dracula and found it very sad, because Dracula is clearly so lonely.

Maybe things could have been different if those Serbian villagers had given Petar Blagojevi? a chance to talk. Maybe he would have gone to his rest if they’d given him back his shoes. Or, perhaps, he was just lonely.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.