Celine Dion

‘Think Twice’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number One on January 29, 1995

1. Don’t think I can’t feel that there’s something wrong

I try my best to be a Cool Dad and keep up with what’s happening in pop music. For the most part, I do an okay job of this, by which I mean that I don’t embarrass my offspring too much by having bad opinions or saying, “What’s this rubbish? Call this music?”

Occasionally, however, I will say something about music that shows how different an era I hail from. For example, sometimes I will say, “Hey, did you hear what’s Number One this week?” This will be met with blank faces. Kids today don’t pay attention to the charts. They’re not even sure what “the charts” are. The Spotify streaming charts? YouTube’s Weekly Top Music Videos? The most viral songs on TikTok?

For people of a certain age, “the charts” is a singular institution, an authoritative ledger of the best-selling records each week since the 1950s. And this isn’t just a list of songs. It is an archive, a testimony, a time-lapse video of evolution in progress. Flicking through the charts in order, you can see songs wax and wane in popularity, climbing to immortality or falling to oblivion. A new winner crowned each week, a new king for seven days (or longer if you’re Bryan Adams), before they are slaughtered and replaced with someone younger. The charts tell a story, and the story is about us.

Or at least they used to tell a story. At some point in recent years, the chart narrative has become garbled, confusing. More and more, it is just a list of songs with no narrative.

When did it fall apart? Was it when Ed Sheeran took every spot in the Top 10? When streaming figures were counted and YouTube oddities like ‘Pen-Pineapple-Apple-Pen’ reached the Billboard Hot 100? Maybe it’s when the Official Chart Company started to include ringtones, allowing Crazy Frog to reach Number One?

It’s hard to pinpoint when the charts died, but we know when it stopped telling its most compelling story—the song that enters in the lower reaches and slowly journeys to the top. That story ended on January 29, 1995, when Celine Dion’s ‘Think Twice’ became the last old-fashioned Number One.

2. You’ve been the sweetest part of my life for so long

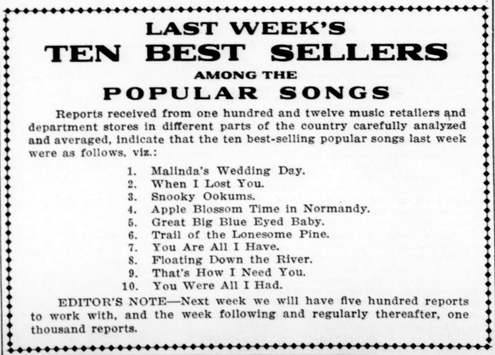

The idea of a popular music chart began in the States just before World War I. Billboard magazine was a vital part of the American entertainment scene, and the 1910s saw them increasingly focus on music entertainment. Records existed but weren’t yet a mass-market commodity. Instead, folk were more likely to buy sheet music of popular songs and play them at home.

In July 1913, Billboard contacted 112 retailers around the United States and asked them for their best-selling songs of the week. Using this information, they compiled the first chart of music sales.

Billboard became a world authority on chart compilation, although their methods were a little scattergun. By the 1940s, they were producing a variety of charts, each based on different statistics: record sales, jukebox plays, radio plugs, industry self-reported figures, and general vibes. These were useful for people in the industry, but didn’t answer a simple question: what was the most popular song of the past week?

Meanwhile, in London, young men were returning home from the war, only to find that their old jobs had vanished. Employers were duty-bound to rehire where possible, but many of those companies simply didn’t exist in post-Blitz, ration-hit Britain.

One returning soldier was a Cockney named Percy Dickins. Dickins had left school at 14 and worked as a messenger boy at Odhams Press, home to illustrious publications such as Ideal Home and Horse & Hound. He’d risen to a role in the advertising department, but paper rationing meant that these magazines no longer had space in which to print ads. Odhams shuffled him around, getting him to work odd jobs on their music newspaper, Melody Maker.

Dickins was a musician himself and used his newfound spare time to gig on the London scene, where he befriended everyone on the scene, including owners of both record shops and record labels. When rationing eased and Melody Maker needed advertisers again, Dickins became one of the most successful admen in the music business. He was so successful, in fact, that he was headhunted to help relaunch a rival newspaper called Accordion & Musical Express (accordions having once been all the rage). The revamped publication was called New Musical Express, or simply NME.

NME published several of Billboard’s music charts, including a list of the most-played songs on British radio and a ranking of “most popular songs in Britain” using an undocumented methodology. The charts were contradictory and confusing, with no clear narrative to them.

Dickins saw an opportunity. If NME could compile a definitive British chart, they would have a unique feature that would drive readership. It would also encourage record labels to advertise in the paper—if you had a disc at Number One, why not take out a big advert right next to the chart? Everyone was a winner.

And so, in November 1952, Dickins contacted a few dozen record store owners, asking them to name the twelve best-selling records of the past week, ranked according to sales. He then crunched this data together and produced a list he called the Record Hit Parade. This was a ranked Top 12—although it was actually a Top 14, as there were ties at Numbers 8 and 11.

Britain (and possibly the world) had its first Number One song based on record sales: ‘Here In My Heart’, the debut record by Al Martino.

Over time, NME’s Hit Parade came to be seen as the authoritative charts. Even Billboard eventually took note of Dickins’ approach and, in 1958, started publishing the Hot 100, which also offered a definitive, all-genre chart for the entire country. The charts stopped simply being a barometer of taste and started to become a tool for taste-making. A Number One song was inherently special, and the goal for every artist was to top the charts.

Chart-watching became an integral part of music fandom, especially when BBC began broadcasting Pick Of The Pops in 1958, a radio show featuring a Top 20 countdown. This was followed by Top Of The Pops in 1964, which arrived at the height of Beatlemania and a golden age of pop music.

Chartwatching turned pop music into a kind of sport. You’d tune in for the weekly chart and see if your team was rising or falling, much like a football team in the league. The excitement when they climbed ten places; the dread when they were a non-mover; the despair when they started falling. When your favourite song reached Number One, it proved that you had impeccable taste. When a song you hated topped the charts, it just showed that you were surrounded by idiots. Either way, you were part of a community.

Every song, good or bad, had to battle its way to Number One. Debuting at the top was vanishingly rare. Even The Beatles only managed it once, and that was with ‘Get Back’, one of their final singles before splitting. Almost every other Number One in history had to do it the hard way, and that was part of the fun.

3. It ain’t easy when your soul cries out for higher ground

How reliable were the charts? Short answer: not very.

By the 1960s, rival publications such as Melody Maker, Record Mirror and industry magazine Record Retailer were compiling and publishing their own charts. Each used the same basic method as Percy Dickins: make a panel of record sellers around the country and ask them to submit weekly sales figures. NME and Melody Maker each had panels of over 100 shops; Record Retailer only polled 30 outlets but was seen as having a more rigorous methodology. Record Retailer even introduced the idea of an independent audit of their charts—which they did in 1963, nearly 10 years after Percy Dickins’ first Hit Parade.

The BBC tried to remain impartial, so they created a weekly average of the charts from each publication. This occasionally meant some weird anomalies such as August 28, 1968, when Top Of The Pops announced a three-way tie for Number One between The Bee Gees, The Beach Boys and Herb Alpert.

(Chart history has been retrospectively rewritten since then. NME are recognised as the official chart for the 1950s; Record Retailer is accepted for most of the 1960s; nobody talks about The Night Of The Three Number Ones.)

In 1969, the music industry moved towards a unified chart created by an independent organisation. This chart drew from a panel of 250 shops, giving the most accurate overview so far. However, there were still problems. Small retailers, especially those that sold more esoteric records, were still overlooked. Worse yet, the panel didn’t include a single Woolworths, despite that chain being one of Britain’s biggest music retailers.

The biggest problem of all was lying. Everybody involved in the charts lied constantly, starting with the chart organisation itself. They claimed that the identities of panellists, known as chart return shops, were top secret and therefore immune from interference. But record promoters knew where most of the chart return shops were, and they’d send “customers” to buy dozens of their records from those shops.

Shop owners themselves would occasionally lie about sales figures, either because they’d been bribed or because they were trying to shift underperforming stock. The biggest liars of all were the shop assistants, who did the manual work of tracking sales and filling in weekly forms. They would lie just for the hell of it; bored teenagers abusing their power just to get their favourite band on Top Of The Pops.

Martin Belam wrote a great blog about the everyday corruption behind the charts:

The heyday of chart hyping was apparently in the 1970s, when the charts were collated using physical books, or sales diaries, from each chart return shop. One music industry old-timer who I used to know told me that it was quite common for the sales reps from the companies to collect the books from the shops, and then all sit down in a pub together on Friday lunchtime and concoct between them the sales records for a whole region. He also once boasted of getting a single into the top forty when they had only actually pressed up enough vinyl to send promotional copies to radio stations, and the label in question didn’t have a distribution deal in place to even get the record into shops.

And yet, a kind of truth always emerged from the charts. Fraud and fiddling did have some impact, such as getting underperformers into the Top 40, or helping Rod Stewart keep The Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save The Queen’ off Number One. But you couldn’t manufature a hit entirely out of thin air. When a single climbed up the charts, it meant that people were genuinely excited about the song.

To take a random example: Tubeway Army’s ‘Are Friends Electric?’ was a song that people were slow-burned to Number One in the summer of 1979. ‘Are Friends Electric?’ was released on a limited run in May 1979 and charted at Number 71, before slowly climbing to Number 25. This was enough to get Tubeway Army on The Old Grey Whistle Testand Top Of The Pops, leading to public fascination with Gary Numan’s robotic persona. The single was resiussed on a bigger run and surged to the top of the charts, almost two months after its first release. This was an exciting journey for fans, and the almost every other number one took the same route: ‘Mamma Mia’ (which took eight weeks to get to Number One), ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ (four weeks) and ‘Ernie, The Fastest Milkman in the West’ (five weeks).

Jarvis Cocker said in his autobiography:

The UK Pop Charts used to be a crazy collision of rampant commerce & grass-roots democracy: people ‘voted’ by buying records & then watching their progress up the charts. It was a national pastime—I can even remember kids bringing radios to school so they could hear the midweek chart positions at break time. That’s taking an interest. It was absolutely mainstream & commercial but also—crucially—anyone could take part. Strange things could happen.

4. Baby this is serious

So, where did it all go wrong?

First, let’s talk about when it went wrong. The UK charts underwent a major change in 1983, as Gallup took control and launched a new data-gather-system. Gallup increased their panel to 1,000 retailers, and started capturing electronic point-of-sale data from barcode scanners. Every Friday, that data was transmitted via modem to a central computer in London, and the vast, hulking machine would grind the figures into a weekly Top 40.

Up until the Gallup era, there had been 512 different Number One songs, stretching back to Al Martino in 1952. Of those, only fourteen (including Al Martino) had debuted at the top spot. The other 498 had started lower down and climbed their way to the top, sometimes over the course of months.

The Gallup era saw things speed up a little. Duran Duran went straight to Number One in 1983 with ‘Is There Something I Should Know?’ and Frankie Goes To Hollywood repeated the achievement a few months later with ‘Relax’. Band Aid went straight to Number One at Christmas, and the rest of the decade saw a number of charity songs enter the charts at the top.

(Fun fact: the next non-charity song to go straigh to Number One? Jive Bunny.)

Most artists still faced a tough journey in the Gallup era. Dead Or Alive had a record chart run with ‘You Spin Me Round’, which squeaked into the Top 100 in November 1984, lingered there for months, then charged to Number One in March 1985—a 17-week wait for success.

The early 90s saw some relatively minor changes with massive repercussions. Singles were only eligible if they were sold above a minimum price. Bizarrely, this meant that cassette single sales weren’t counted for most of the 80s, as they typically retailed for £1.99. The minimum price was lowered, which opened the doors to deep discounting. Labels figured out quickly that selling your singles cheaply, especially on release weekend, would lead to a surge in chart position.

Charts started looking drastically different. Singles went straight to Number One with increasing frequency—there were fourteen such hits between 1991 and 1994. When ‘Saturday Night’ went directly to Number One, Whigfield became the second artist to have their debut single go straight to the top of the chart. The first artist? Al Martino back in 1952.

That year also saw the launch of the Chart Information Network, which took over from Gallup and extended its panel to 2,500 shops, eventually including almost every shop. In a way, this made the charts much more transparent. Bored teenagers couldn’t pretend that their favourite band had sold 200 copies last week. The charts were based on cold, hard, incontrovertible data. They were fully professionalised.

Unfortunately, this created the same problem you get in any sport that’s overly professionalised. You end up with moneyball, talent and intuition replaced by spreadsheets and investors. When the charts were chaotic and gung-ho, they were impossible to control. Now that everything was more organised, it became easier to place a song at Number One. The right mix of radio promotion, discounting and in-store promotions essentially guaranteed a Week One hit.

Between 1995 to 2000, only fifteen chart-toppers didn’t debut at Number One, and almost all of those debuted within the top three. Between June and September of 2000, the UK had a new Number One each week, and every one of them was a new chart entry.

This wasn’t a disaster for music, but it was the end of the charts as a major cultural institution. What did “Number One” mean in a world where there’s a new song at the top each week?

Top Of The Pops had been an immovable part of Thursday nights for over thirty years until 1996 when it was unceremoniously shunted to Fridays to compete against Coronation Street. Its days were numbered. There was no further need for a weekly show about the Top 40. The sport had gone from the charts.

5. Are you thinking ’bout you or us

A good story needs a good ending, and we did actually get one, even if we didn’t know it at the time.

October 1994 saw the first-ever consecutive Number One debuts. First was Whigfield with ‘Saturday Night’, followed by chart behemoths Take That, scoring their second instant Number One of the year with ‘Sure’.

All eyes were on Robbie & Co, and few noticed Celine Dion releasing her new single. Dion wasn’t a household name yet; her cover of ‘The Power of Love’ had made the Top 10 at the start of the year, but follow-up single ‘Misled’ peaked at Number 40. ‘Think Twice’ spluttered into the charts at Number 54, one place behind fellow new entrants, The Jesus & Mary Chain.

Nothing happened for a few weeks, but ‘Think Twice’ picked up some radio play and crawled into the Top 40, reaching a respectable Number 30 by November. Power ballads were already represented in the Top 10, thanks to Bon Jovi’s ‘Always’ at Number 2. ‘Always’ looked like a long-shot contender for Xmas Number One; ‘Think Twice’ looked like landfill waiting to happen.

And then, something changed. At the start of December, Bon Jovi slipped down the charts, while Celine Dion surged. On the final chart before Christmas, ‘Think Twice’ had ascended to Number 5, only held off the top by a Power Rangers novelty record, East 17’s ‘Stay Another Day’, and soon-to-be festive mainstay, ‘All I Want For Christmas Is You’.

Come the big day, Celine got pushed down to Number 6, overtaken by ‘Cotton Eye Joe’ and a new Oasis song. Nonetheless, it was a pretty impressive run for a song that had started out so poorly.

Except Celine wasn’t quite finished, and neither was ‘Think Twice’. The song suddenly became omnipresent on TV and radio; it was impossible to avoid Celine’s howling melodrama or her egregious attempts to rhyme “serious” with “you or us”. There’s an intangible threshold where a song goes from being a mere song and becomes a hit, something that everyone knows and nobody will ever forget. Around New Year’s Day of 1995, ‘Think Twice’ seemed to pass that threshold.

But now the problem was that she couldn’t seal the deal. On January 8th, 1995, ‘Think Twice’ climbed to Number 2 in the charts, failing to shimmy past Rednex and their ‘Cotton Eye Joe’. Both songs remained at the top of the charts for the next three weeks, despite massive competition from songs like ‘Here Comes The Hotstepper’, ‘Set You Free’ and Boyzone’s ‘Love Me For A Reason’.

The smart money would have bet on Celine missing out on the top spot. It had been fifteen weeks since the song appeared, longer than almost any other chart journey in history. She’d already found a second wind, and a third. She’d never get a fourth.

The smart money would have lost. On January 29, 1995, the new UK chart confirmed that ‘Cotton Eye Joe’ had fallen to Number 2, and ‘Think Twice’ was the new UK Number One. A crown first worn by Al Martino in 1952 was now passed to Celine Dion.

Some sources credit her with the longest-ever chart run to Number One, but her 16 weeks is just shy of the 17 week wait for ‘You Spin Me Round’ and Jennifer Rush’s original ‘The Power of Love’ (although Celine spent more of her run in the Top 40). At any rate, all records were smashed in 2014 when Ed Sheeran waited 19 weeks to get to the top, although nobody was paying as much attention to the charts by then.

Celine Dion definitely wins the award for performing the last old-school chart ascent to the top. Other records, like Ed Sheeran’s, might have performed the same journey, but it’s not the same when it’s just one song making the trip. The magic of the old-school charts was that you had 40 songs, all competing at the same level for the same prize. Every week offered new intrigue, new speculations about risers and fallers and who was on course towards immortality. It was broken and it was corrupt, but by god it was compelling.

Perhaps this is the perfect anthem for the end of the old-school charts. Overwrought, melodramatic, compelling, inane (that “serious”/”you or us” rhyme), deeply earnest, fundamentally silly, ultimately disposable. It mattered so much for a while, and then it didn’t matter at all. ‘Think Twice’ is how the charts sounded, back when the charts were good.

Enjoyed this? Members can keep reading over at the Patreon.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

I don’t remember quite when it happened, but another change that ruined the charts was that radio wouldn’t play singles until the week of their release, then probably in the early 90s they would start previewing them weeks in advance. From that point onwards, debuts at number one became the norm rather than the exception, and I, for one, lost interest.

Spot on Jeremy. Extended radio previews played a huge role in changing the charts.

This was an incredibly well-researched piece thanks! I so love the story of songs and albums, and how the charts often reflect their journeys (and – in turn – our journeys as the fans). I am sad for the homogenisation of music and the downfall of the thrill of the charts. It all feels so meaningless now, what with the formulas used to combine digital and physical sales. But it was certainly eye-opening to read of the ‘cheating’ way back when as well. Well done again.

Cheer Ben!

I personally cannot stand Celine Dion, but this song reminds me of an unrequited love from that time, as she loved the song.

yns9kt

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.