Flowered Up

‘Weekender’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number 20 on May 3, 1992

Something that’s changed—for the better—since the 90s is our relationship with celebrity.

Stars are no longer these distant, ineffable beings. Thanks to the ceaseless Truman Show-esque nature of social media, we can peer into their lives and see that they really are just like us.

And sometimes that allows us to relate to their humanity a little better. Britney Spears is the prime example here. In recent years, people have developed a deep empathy for this complex, vulnerable woman.

Which makes a change from the days when celebrity gossip was a bloodspot, and Britney was hunted without pity. She seemed so alien back then, this beautiful superstar, that it was hard to imagine her experiencing the grief and sadness of a normal human life.

We used to love celebrities going off the rails. Sometimes, it was the joy of tutting judgmentally at them (Amy Winehouse, most female celebs), while other times we wanted to live vicariously through their stories of excess and debauchery (Pete Doherty, most male celebs).

In the era of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, we loved hearing about how far people could go. How far it was possible to go. How long you could make the party last.

Smash your hotel room. Break out of rehab and go on a bender. Spend your advance on coke. Want to be a legend? Seek immortality in The 27 Club. Be our hero. Bleed for us.

This appetite for destruction is part of the reason that the music press fucking loved Flowered Up.

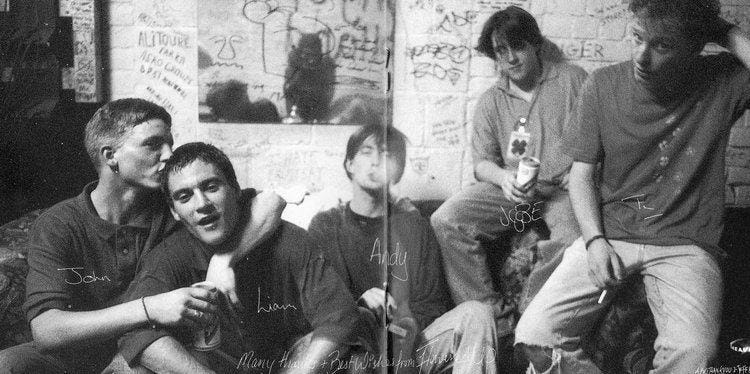

Flowered Up were a bunch of working-class kids from a London housing estate who had a titanic capacity for drugs and violence.

The early Flowered Up gigs are the stuff of legend, with the band and the audience competing to see who be most off their faces (the band always won.) They got themselves on the covers of NME and Melody Maker before signing a deal—a feat that can probably be attributed to them sharing their drugs with music journalists.

There are endless stories about Flowered Up getting banned from hotels, banned from venues, banned from cities, getting beat up, getting locked up, running from the cops.

And the drugs. The endless drugs. When London Records offered them a £1,000,000 contract, the band celebrated by pulling out a gigantic bag of coke, stabbing it with a knife, and then writing F U in giant letters on the boardroom table.

The resulting album, A Life With Brian, was deemed to be a flop (although that’s actually a bit harsh, it’s not terrible) and London quickly dropped them. But the band found a new home at Heavenly Records and convinced them to put out a 12-minute rant about part-timer clubbers who work Monday to Friday. There’s no reason to ever leave the party, you fucking causals, was the message of the song`, with Liam Maher ranting like Prince Prospero in Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death”.

That song was called ‘Weekender’ and it is kind of a masterpiece:

‘Weekender’ was critically adored when it appeared. The stunning video/short film got a lot of airplay whenever MTV had a spare 15 minutes in the schedule (usually at about 2am).

But the EP was overshadowed by its own infamous launch party. A party so epic that it had a name: Debauchery.

The story behind the Debauchery party goes like this: Barry Mooncult, the Bez-style dancer in the band, was also a painter-decorator on the side. He was doing a job for a dodgy London millionaire who got lifted for tax fraud.

Barry was left with the keys to a vacant mansion.

And so, this mansion got turned into a vast nightclub. The ground floor was turned into a dancefloor with people like Paul Oakenfold on decks. The first floor was a hangout to drink and get high. The attic was a non-stop orgy. The band spent most of the party in the jacuzzi, naked except for top hats.

Around 1,000 people attended the party, which lasted somewhere between three hours and a week (accounts vary). The Mondays and Primal Scream dropped by, as did Kylie, Kirsty McColl and the Guildford Four. Britain’s hottest young novelist, Hanif Kureishi, called in and ended up writing about the party in his next book, The Black Album.

Everyone who remembers the party (and is willing to talk) says that it was like something that hadn’t been seen since the days of Caligula.

The band themselves don’t remember the party. By 1992, they had moved on to heroin and it was eating them alive.

The old system of celebrity worship was a form of human sacrifice. And sacrifices can’t survive. It ruins the ceremony.

That’s why The 27 Club was the best possible outcome. You get to leave this world as someone young, beautiful. People mourn your untapped talent, rather than taking the piss out of your misjudged late-career reggae album.

Flowered Up had the worst possible outcome to their story. The band largely imploded after ‘Weekender’ and all of their subsequent attempts to make music failed.

(Apart from Tim “the posh one” Dorney, who went on to form Republica.)

Liam and Joe Maher, the brothers at the heart of the band, stopped being party legends and became old-fashioned junkies, intermittently homeless and relegated to the absolute bottom of society. Around 2006, the rest of the band tried to get back together to help the Mahers back on their feet.

But it was too. Liam died of a heroin overdose in 2009. Joe struggled to get clean, but he went the same way in 2012.

It’s easy to criticize today’s oversharing celebrities. The whole Kardashian/Paul Brothers thing is exhausting. We don’t need to know every detail of a famous person’s life.

But I think this intimacy has destroyed the romanticism around problematic behaviour. There used to be something mystical, almost shamanic, about creative self-destruction. Like the artists were dying for us so that we could be reborn in them.

Now, I think we’re more likely to see what’s really going on. Addiction and mental health distress aren’t sexy, they’re relatable and extremely sad. And today’s young people get the message that it’s okay to leave the party when the party stops being fun.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!