Suede

‘Animal Nitrate’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

Number 7 on February 28, 1993

1.

Here’s a common story among men my age. In my early 20s, I threw out almost everything I had acquired during my teenage years, starting with my big pile of Melody Maker and NME back issues.

“Ha!”, I said, “when will I ever want to re-read the 1995 Melody Maker with Menswear on the cover where the band split up right in the middle of their interview?”

And the answer was: sometime in my mid-40s, and I would pay €15 on eBay for a second-hand copy.

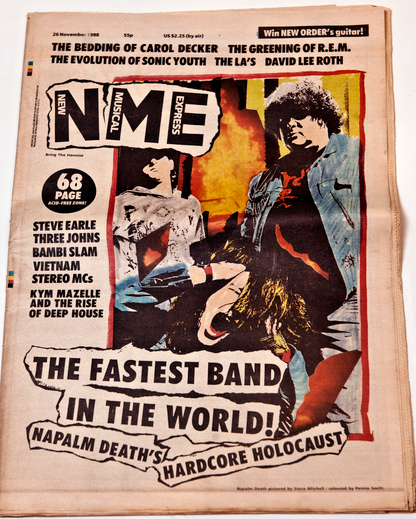

It’s strange to hold a mid-90s Melody Maker in your hands again. It was such a weird magazine. Physically weird—both MM and NME were printed on A3 paper, making them much bigger than a modern tabloid. The paper itself was absolute dogshit quality, and the ink would smudge while you read them, hence the nickname, “the inkies”.

Both magazines baffled me as a kid. The newsagent kept them down flat at the bottom of the rack, in between The Sun and Racing Post, so the cover star would stare up at me as I reached for my comics. All of the featured bands sounded made up.

I don’t remember the first time I bought an issue. Someone on the cover caught my eye—probably a grunge band—and I thought, “What the hell. Let’s see if this is as good as 2000 A.D. or Amstrad Action.”

Before I knew where I was, I had started buying both magazines every week, obsessively reading them from cover to cover.

This wasn’t about the music. We’re talking pre-Spotify days, so I couldn’t just play the tracks mentioned in the magazines, so I was reading reviews of records that I had never heard and would probably never hear.

No, this was about the story. The inkies reported the music scene in soap opera style, with heroes and villains, and endless plot twists. Everything was hyperbole, and very little of it was related to the music (favourable press coverage was usually a sign that the band had given the journalist some of their drugs…or something else.)

Most bands hated this and hated the journalists, which is fair. But I absolutely loved it and desperately wished I could be one of them.

2. Now you’re taking it time after time

Melody Maker started as jazz magazine in 1926, and did quite well until the rock’n’roll era. They refused to cover this teen fad, which left an opening for a new magazine: the New Musical Express.

After that, Maker remained in NME’s shadow, although they did manage some notable scoops, including the 1972 interview in which David Bowie said, “I’m gay and always have been.”

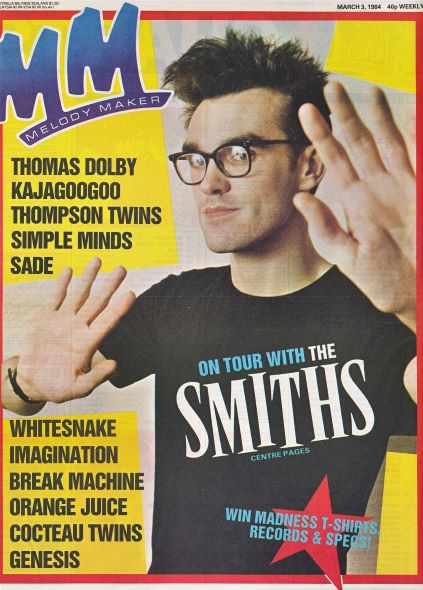

Melody Maker’s biggest cultural moment happened in early 1984. The magazine was in the middle of a disastrous pivot into the mainstream pop market, with bands like Duran Duran and Wham! on the cover of millions of unsold issues.

Editor Michael Oldfield (no relation) decided to take a break, so he booked a two-week holiday and handed the reins to Allan Jones. Jones had one instruction: do what you like, as long as you put Kajagoogoo on the cover.

Allan Jones had been hired as a teen in 1974 after writing a letter that said, “Melody Maker needs a bullet up its arse. I’m the gun – pull the trigger.” Now, it was 10 years later, and he was writing puff pieces about The Thompson Twins.

Finally, here was his chance to pull the trigger. Jones cancelled the Kajagoogoo shoot and instead gave the front page to an up-and-coming indie band from Manchester.

Oldfield was furious—until he saw the sales figures. Eager Smiths fans had grabbed every copy they could find, and now they were desperate for more.

Jones and Melody Maker had achieved every music journalist’s dream: find an obscure band, put them on the cover, watch them go supernova, and brag about how you spotted them first.

3. So in your broken home

Melody Maker often tried to repeat this trick, but never with the same success.

(In 1996, I paid good money to read a three-page feature about how Northern Uproar were going to be the next Oasis. I would still like a refund.)

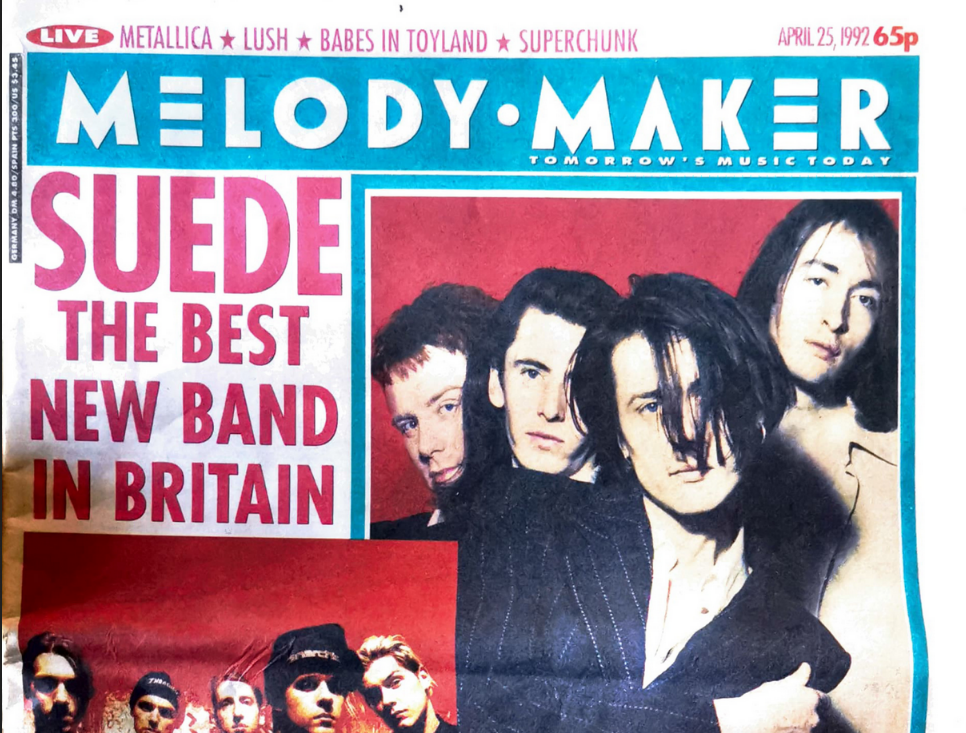

Maybe the biggest, most outrageous attempt to have another Smiths moment happened in 1992. Journalist Steve Sutherland convinced the editor (Allan Jones himself, who was promoted shortly after his Smiths cover) to throw everything behind a band that had yet to release a record—not even a single.

In some ways, this was an act of desperation. British indie had been in the doldrums since The Stone Roses, and American rock was running the show. Melody Maker was lucky enough to have Everett True on the team, who got them exclusives with Kurt Cobain, but they desperately needed local bands that they could interview, study, champion, mould, and—most importantly—score drugs from.

They needed a scene. They needed a setting for the soap opera.

And so, Steve Sutherland wrote about this band who hadn’t released a single note of music, calling them:

“The most audacious, androgynous, mysterious, sexy, ironic, absurd, perverse, glamorous, hilarious, honest, cocky, melodramatic, mesmerising band you’re ever likely to fall in love with.”

…while the cover declared them “The Best New Band In Britain”:

So, a lot was riding on Suede. And the omens were good! Their first single, ‘The Drowners’, is a knockout, a lascivious glam rock throwback with overtly queer lyrics. It deserved to be a massive hit.

But it wasn’t.

‘The Drowners’ charted at Number 49 in May 1992, one place behind the new Craig McLachlan single, and 38 places below The Levellers, who were exactly the kind of band that Melody Maker liked to ridicule.

Suede’s next single, ’Metal Mickey’, peaked at Number 17, which is respectable but hardly a sign of The Best New Band In Britain. Suede went a little quiet after that as they began recording their debut album.

1993 would be the last chance saloon for Suede, Steve Sutherland, Melody Maker, and possibly the entire British indie scene. If a hit record didn’t arrive soon, indie would be swallowed whole by American alt-rock.

Luckily, Brett Anderson has high hopes for Suede’s next single: the epic piano ballad, ‘Sleeping Pills’.

4. The delights of a chemical smile

Sony said no to ‘Sleeping Pills’. A fine song, but would have never have been a hit single. Instead, Sony pushed for the more upbeat, hook-driven ‘Animal Nitrate’.

Suede weren’t keen on the idea, but they were too burned out to argue. So they got a big bag of coke, shot a cheap video, and went back to touring.

But Sony were right, and ‘Animal Nitrate’ debuted in the Top 10, becoming a genuinely popular song. Suede were invited at the last minute to perform ‘Animal Nitrate’ at The Brits, which helped cement them as serious contenders. Suede, the debut album, charted at Number One and went on to win the Mercury Music Prize.

All of a sudden, Suede were happening.

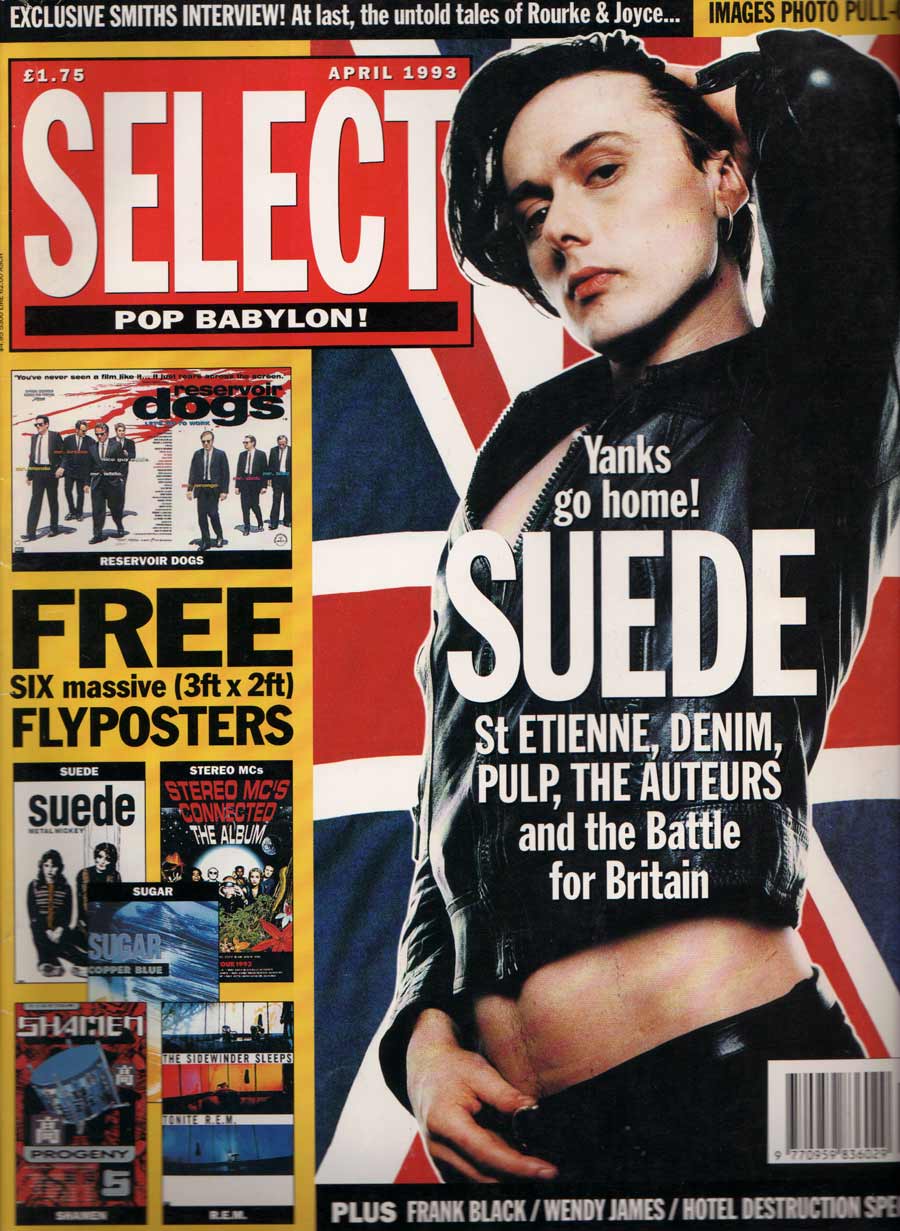

And it wasn’t just a band—it was a scene. Other bands with a similar aesthetic were releasing great records, and most of them were hanging around the pubs of North London (and sharing their drugs with journalists). Select celebrated the new scene in a cover that effectively announced the birth of Britpop.

Vox magazine (a spin-off of NME) did a fun bit of gonzo journalism around the time of ‘Animal Nitrate’, where they invited Morrissey along to a Suede gig as a kind of passing-the-torch exercise. Moz dismissed them with one of his finest Moz-isms (“He [Brett] will never forgive God for not making him Angie Bowie”), but a few weeks later he was covering ‘My Insatiable One’ in his live shows.

5. Now he has gone

I finally made it to London in the early 2000s, shortly after 9/11, and found the entire Britpop world was gone.

Camden was all tourists now. Oasis were turning into Aerosmith; Blur were going a bit Pink Floyd. The only cool guitar bands were people like The Strokes and The White Stripes—all Americans.

The music press might have been the first real victim of the internet age. By the time Napster arrived, Melody Maker was on life support, and the desperate attempts to stay relevant turned it into a laughing stock.

The final issue featured Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst. There was no fanfare, no look back on 74 years of history. Just a quiet announcement that Maker would be merging with NME, which is the publishing equivalent of euthanasia. NME became a general culture magazine, then a free magazine, and is now a Buzzfeed-style website.

Re-reading old issues now, we’re probably better off without the inkies. They were insane: power-drunk journalists writing unhinged rants about pop records, making and breaking careers on a whim. On the whole, they probably did more harm than good.

God, it was fun though, especially when you finally heard the current flavour of the week and it turned out to be something like ‘Animal Nitrate’.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.