4 Non Blondes

‘What’s Up’

Highest UK Top 40 position:

#2 on July 18, 1993+

1. 25 years and my life is still

Spring of 2017 was a tense time. Trump was settling into the White House, Brexit was going full steam ahead, and the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements were at a crucial inflection point.

There were no bystanders anymore. Everyone had picked a side, everyone was angry, and it felt as if we were on the brink of full-scale societal collapse.

And then, Pepsi released an ad with Kendall Jenner.

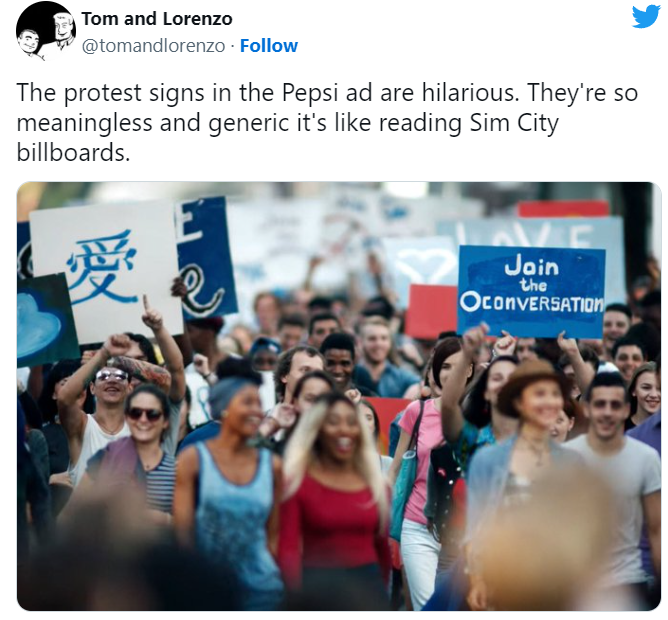

The ad shows a group of young, beautiful, ethnically diverse people marching in a big street protest. The focus of the protest isn’t clear—all of the banners say things like PEACE and RESPECT and #JoinTheConversation—but a big, meaty wall of cops is still prepared to shut this down.

Our hero, Kendall Jenner, is in the middle of a fashion shoot when she sees the protester. Jenner rips off her wig, joins the crowd, and instantly becomes their leader.

Did Kendall throw the first brick? No. Instead, she takes a delicious can of Pepsi and offers it to one of the cops. He takes a sip and smiles. The other cops smile at him. The protestors high-five each other. World peace is achieved.

The internet’s reaction to this ad was…not positive.

There’s a lot to unpack here, but one egregious detail was the vague nature of the protest:

In 2017, people were protesting about well-defined issues: racism, sexism, institutional violence, the resurging far-right, impending climate catastrophe. Social media was full of people eloquently explaining what they were angry about.

So what’s the point of an ad that shows people protesting about… nothing?

2. Trying to get up that great big hill

Anyway, the way people felt about that Pepsi ad is how I’ve always felt about ‘What’s Up?’.

By 1993, grunge was deeply entrenched in the mainstream. Grunge had a loose political energy that was part punk (anti-establishment and anti-capitalism) and a little hippy (eco-conscious and socially progressive), but there was no clear Grunge Political Ideology, apart from a vague resentment of The Corporations.

4 Non Blondes were not quite grunge, but they were grunge-adjacent enough to fit into the zeitgeist. And their styling was certainly the kind of thing that was only acceptable during grunge (especially those dreadlocks).

When ‘What’s Up?’ blasted onto the airwaves in 1993, it felt like more of the grunge-ey political discontent, but delivered by someone who can actually sing.

Linda Perry’s voice is huge. On ‘What’s Up?’, she sounds like Eddie Vedder if Eddie Vedder had spent twenty years getting singing lessons from Whitney Houston. Perry’s voice dips and dives throughout ‘What’s Up?’, soaring across the “hey-yay-yey-yeah”s of the chorus, cracking like lightning when she asks “what’s going on?”, and summoning a hurricane when she screams “REVOLUTION!”

But a revolution against what?

‘What’s Up?’ lyrics themselves have a strangely non-specific quality to them, as insubstantial as something written by ChatGPT:

I wake in the morning and I step outside

And I take a deep breath and I get real high

And I scream from the top of my lungs

“What’s going on?”

Plus, they’re written in this narrow first-person perspective, with almost every line beginning with “I”. The song doesn’t mention anyone or anything in the exterior world, or even name any specific concepts. It’s a song about feeling angry about, y’know, stuff or whatever.

This is not inherently a bad thing—there are plenty of great songs about abstract ennui. However, the anthemic quality of ‘What’s Up?’ makes it feel like a big state-of-the-nation protest song, like there should be some kind of manifesto here.

Things aren’t helped by the fact that the chorus mentions perhaps the greatest state-of-the-nation protest song of all time, Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On’.

Maybe it’s unfair to compare these songs. ‘What’s Going On’ was created in the context of fraught political tensions and a violent battle for civil rights—everyone already knew what was going on.

To judge ‘What’s Up?’, we have to put it in a 90s context and the politics of grunge.

3. For whatever that means

Grunge, like a lot of youth-oriented cultural movements, was mostly about being angry at your parents.

In the early 90s, American Gen Xers were furious at the generation before them. Boomers had spent their teens and 20s enjoying peace, love, drugs and casual sex; when Boomers turned middle-aged, they voted for Reagan and pulled up the ladder behind them.

In his seminal 90s novel, Generation X, Douglas Coupland wrote:

“Sometimes, I’d just like to mace them. I want to tell them that I envy their upbringings that were so clean, so free of futurelessness. And I want to throttle them for blithely handing over the world to us like so much skid-marked underwear.”

The 90s were The End of History, a new age of neoliberal, post-Cold War peace and prosperity. But that soon felt oppressive to Gen X, who saw nothing ahead except a monotonous life as a drone in the capitalist machine.

In the paper Bleached Resistance: The Politics of Grunge, Thomas C Shevory argues that this was fundamentally reactionary. He says:

That the older generation stole the future and saddled X-ers with what are left of the crumbs was the central theme of Coupland’s book. [Coupland] largely ignores the specificities of class, race, and gender. As Andrew Cohen has observed, “What Coupland’s young people . . . share is a peculiarly conservative and middle-class disappointment—a sense of entitlement gone sour”

Basically, you can’t feel horrified by middle-class life unless you yourself are middle-class. Grunge politics only spoke to a certain group of people, most of whom were white, male, and from financially stable backgrounds. People from outside those groups did not share grunge’s concerns.

Shevory goes on to write:

“While Kurt Cobain wasn’t middle-class, his internal conflicts spoke to a generation of middle-class youth who have found their reduced economic prospects to be intolerable. In response, grunge offered what Sarah Ferguson has labeled the “politics of damage…being damaged is a hedge against the illusory promises of consumer culture.” At the same time it “offers a defense against the claims of gangsta rappers and punk rock feminists”. Damage entitles one to a claim of dispossession. At the same time it sanctions an emotional space beyond both resistance and apathy. Early punks knew who the enemy was: authority, order, power, and just about everything else. In the ideology of grunge, the enemy turns out to be the self.”

Living in capitalism is tricky. You might hate capitalism, hate what it does to you, hate what it does to those outside the system. But you also don’t want to leave the system, because capitalism has McDonald’s and Funko Pops.

And so you end up in the eternal liberal paradox, praying for revolution but terrified of change. The unresolved tension becomes internalised, an anxious battle inside your head. You’re always at war with yourself for some undefined reason. You’re angry about… nothing.

4. Just to get it all out what’s in my head

And it’s not like things were all that rosy in 1993.

As mentioned above, this was the week that Mia Zapata was murdered. It was also a year after the LA riots in response to racist police violence. Events likes these would, in 2017, bring popular support to movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, but early 90s grunge kids weren’t that interested.

You can’t really blame 4 Non Blondes for this. As a group of mostly queer women, they were no only aware of the political stakes, but they sang and wrote about it. Songs like ‘Dear Mr. President’ have unambiguous lyrics like:

What kind of father would take his own daughter’s rights away?

And what kind of father might hate his own daughter if she were gay?

But that song wasn’t a hit.

Now, it’s always been hard to sell songs with strong political messages. People will tolerate something with twee platitudes like ‘Imagine’, but they pull back when they hear ‘Working Class Hero’. Even Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On’ avoids having too many specific details.

However, this specific 90s moment is stuck in a strange kind of anti-politics. We’re angry, but not about anything in particular. We can’t figure out what’s bothering us. We’re on the streets, protesting about nothing.

For this moment, ‘What’s Up?’ is the perfect anthem.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this, here are two things you can do next.

Join the list

You’ll get the next big essay in your email. Published every two or three weeks. No spam ever, I promise.

Become a supporter

Support the site and you’ll get exclusive weekly emails about old charts, plus behind-the-scenes notes on each essay.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!